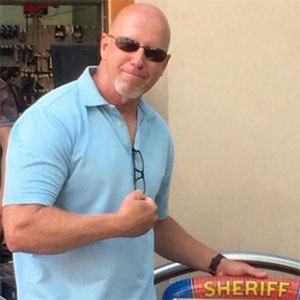

He was the old bull on graveyard shift. He worked west beat and I was the eager young gun on the adjoining river beat, and I loved him. He occasionally wore a brass name tag that read, “Deputy Knarf Oylap.” It was his name spelled backward, and he did it to prove that nobody cared. He also wore one that said, “The Responding Deputy,” because that’s what the newspapers always called him. He had long ago trained management to leave him alone.

He was the only cop in the county who carried a .44 Magnum, the Dirty Harry gun. When we had night qualifications, the barks out of that old roscoe would light up the range. Once the calls died down, we’d meet for coffee in the Forestville Cemetery. I just loved all of his old cop stories. He’d have me howling so hard that I thought I might break a rib.

When I moved to the homicide unit, we remained friends. But keeping in touch got easier when, like a lot of the graying lions, he gave up the decades on patrol to finish things up in court security. His new office was right above the detective bureau, and we were back in the saddle again as if we’d never missed a beat.

When I’d check in, he’d say everything was fine, but I was hearing otherwise. Like a lot of cops, he was having marriage troubles, and I’d heard a rumor that he had cancer. Supposedly, it was nothing to worry about. Still, I did.

He invited me and my wife over for dinner one evening. That was a bit odd, because we’d never done stuff like that before. I remember thinking what a great opportunity it would be to size things up and see how Frank was really doing.

Frank, his wife, and his two handsome and polite preteen boys lived in a tidy, well-kept little condo. We had a nice evening full of friendly, superficial talk. As we drove away, I told my wife, “I think he’s OK,” but I added that I should probably follow things up with a cup of coffee soon. I never did.

Not much later, while working away at my desk, I saw a bunch of detectives, guns in hand, jump out of their chairs and start racing toward the front door. I grabbed my 1911 and followed. As we bounded upstairs, I learned that there was an active shooter in the courts.

I really think Frank’s death was line-of-duty. This job can suck the life out of good people. And all too often, it does.

Ready for anything, we all rounded the entrance to the main hallway. It quickly became all too obvious that we were too late. A group of deputies were huddled together down the hall, talking. One of them was the assistant sheriff. He looked me straight in the eyes and summoned me over with his bony finger. “Frank Palyo is dead from gunshot wounds in that public restroom over there. We don’t know how it happened. You’re in charge.” I kept my game face on, but my heart sank. I’m sure I wouldn’t have gotten the assignment if he knew we were buddies. But I didn’t tell him, and I didn’t flinch.

I’ve seen a lot of ugly death scenes, but this one was really bad. It was a one-stall restroom with gray walls, smooth-tiled to the ceiling. Forensically speaking, that was a matter of good luck. Frank was fully uniformed and face-down on the floor. Much of his brain was evacuated and nearly all of his blood had pumped out.

I delicately worked around him for hours. By stringing up the trajectories of bloodstains and brain matter, I was able to prove that Frank didn’t die at the hands of another. As he stood in front of the small mirror above the sink, he pressed his .44 Magnum firmly against his temple and pulled the trigger.

At autopsy, I remember just staring at him as he lay there, opened up like a canoe. My partner broke the silence: “Hey, Dave, knock it off. That’s not Frank. It’s just meat.”

What I was thinking then is what I still think about today: “Why the hell didn’t I try to do anything?” I had enough information, and I had enough love for this man, too. Frank deserved much more from me.

I’m sure that Frank didn’t consider the fix that he put me in that day. In fact, I know he didn’t plan things at all. He just went to the head to take a piss. I see him, mission accomplished, walking over to the sink to wash his hands. I see him rinse his hands and lean in a bit toward the mirror to look intently at his face, with all of life’s bullshit circling in his head. He rubs his cold, wet hands on his cheeks, and sighs. And then, while straightening the gig line of his gun belt, that occasional thought pops back into his head. But unlike the thousand times before, he glimpses a quick way out. This time he audibly says, “Fuck it.” Frank pulls out his 4-inch S&W Model 29, puts the muzzle up tight against his temple and pulls the trigger. It was just too easy.

Even though they’re not recorded that way (and think about it, they never should be), I really think Frank’s death was line-of-duty. I remember all of his stories. Like with so many of us, it was just too much. This job can suck the life out of good people. And all too often, it does.

You can live 30 days without food, three days without water, three minutes without air, but you can’t live three seconds without hope. Many who “attempt” suicide still have hope. Think of that gal on your beat who pops six over-the-counter sleeping pills and then calls 9-1-1. They’re really only desperately looking for help. Between them and the one-and-doners like Frank, we say that they’re more rational. But I’m not so sure about that.

If the evidence in front of you makes you believe that quitting life is the only way to escape the 24/7 suffering, and if you take all the spiritual stuff out of it, and if your heart believes that things are forever hopeless, I suppose the math could work.

People say suicide is a selfish act. I’m sure that at that weak moment, Frank was only thinking of himself and his anguish. If he could come back for a day and see all the havoc and pain his “selfish” decision caused others and then get a do-over, he would probably still be here today. I know his calculus didn’t include the decades of anguish and pain for his boys. Or that they will surely go through adversities in their own lives, too, and looking at their options, they will remember that the dad they so loved and admired chose thusly. Suicide is too often inherited, and that’s probably one of the reasons why.

I’ve thought a lot about what I would say to Frank if I got a do-over and could meet him for coffee that morning. I think I’d start out with: “Frank, you’re important to me. I want to listen to you and hear everything. Your worries, your fears, your regrets — don’t leave anything out. Please, you can have all of the time you want. We’re good friends and it’s no burden to me.” Then … I’d just listen. You see, like many officers, I doubt Frank ever felt he could tell anyone about his secret pains, and finally feeling safe to do that would be a much-needed salve.

Like I said, I don’t think Frank planned his death, but if I had better perceived all that brought him to that moment, I’d try to help him find the hope that truly was all around him, but that he just couldn’t see. If he’d been able to open up to me, perhaps we could have made an agreement that he wouldn’t take his life that day. Instead, I’d ask him to make a commitment to live with the same result: that from that day on, his life as he knew it was effectively over and he would quit trying to live for his hopeless version of it. I’d then ask him to get up the next morning and spend some time thinking about the day that his boys would be having if he had gone through with it, and to reflect on all of the pain and anguish he saved them from.

I’d continue by encouraging him to choose something to do with his boys on that same day that would make them beam with joy, to resolve to make it a day that the three of them would remember forever. After all, I’d remind him, since his life was “over,” now he was free from all of those burdens and could focus on others. I’d ask him to do this every morning, to pick out someone he loved and then make a concrete plan to do something exceptionally kind and generous for them. I’d add, “And because we’re friends and I care about you, promise me that every morning you’ll send me a note that you have made a plan for that day.”

You see, there’s a secret to life, and because of all the shit that we see and do, we’re especially prone to forget it: What refreshes us, and even what saves us, is our connectedness. Left to its own devices, this job of ours causes just the opposite: disconnectedness. If you get a room full of Ph.D. sociologists, theologians from various faiths, yogis and metaphysicians of all stripes together and then ask them, “What is the meaning of life?” they’ll all agree: The one thing that gives us purpose and a reason to live is relationships. Without relationships, life is meaningless. Our relationships give us meaning, and the hope to keep going every day.

The truth is this: When you go out of your way to invest in others — especially those you love — you’re also investing in yourself. It’s what makes life better. It’s what makes you whole.

So what about you? Even if you have all the saddle time that Frank did, if you can wisely reframe how you prioritize this oft-shitty-but-still-noble job of ours, your closest off-duty relationships — and you — may well flourish anew. And on duty, those sacred opportunities to help real victims in their darkest hours may once again be the salve that invigorates your dying hopes, too.

As seen in the September 2020 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: