In 1940, there were 223 state and county mental hospitals in the United States with some 420,000 patients. By 1955, the resident population had increased to 559,000 inpatients. Since then, the number of inpatient beds in state and county mental hospitals has decreased steadily to about 60,000 today, or about .018% of the current 2021 U.S. population.

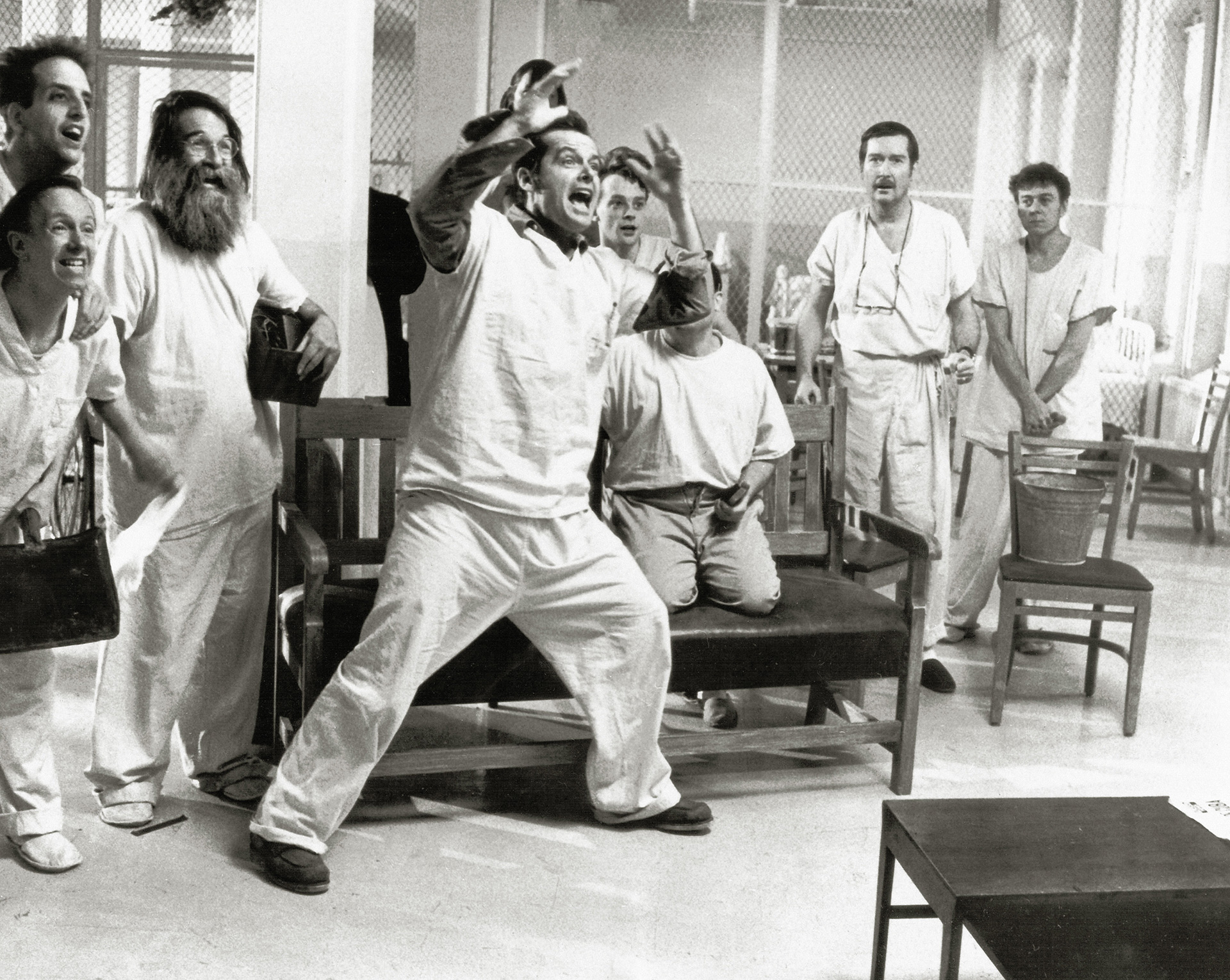

State hospitals emptied their patients onto the streets through the 1970s as the stereotypical mental health hospitals of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest fame were closed nationwide. This led to a severe shortage of inpatient care for people with mental illness, which is nothing less than a public health crisis.

Mental illness has a wide continuum. Nearly one in five U.S. adults lives with a mental illness. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reports that one in 20 adults suffers from serious mental illness.

Approximately two million times each year, people with serious mental illness are booked into jails. About two in five people who are incarcerated have a history of being diagnosed as having a mental illness (37% in state and federal prisons and 44% held in local jails). Currently, 10 times more people with mental health disorders are in jail or prison than in mental health facilities. That means roughly 356,000 inmates are not receiving the care they need.

The rates of the homeless mentally ill have skyrocketed, and jails and prisons that are often at capacity have become the new psych units.

It’s broken

Officers nationwide in metropolitan, suburban and rural agencies have experienced frustration with a broken mental health system that needs a complete overhaul or rebuild.

While large agencies struggle with the mental health crisis, the average American police department is composed of fewer than 25 officers. In fact, 87% of all police departments have just a few dozen officers on their force. How did mental illness, drug addiction and societal failures become the primary responsibility for law enforcement to handle without the resources or training to be successful?

Many calls to the police concern mental health issues, but don’t involve any serious criminal activity. But even when a crime hasn’t occurred, the public — or whoever called 9-1-1 — expects the responding officers to address the immediate crisis.

A study in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine found “1 in 5 (21.7%) legal intervention deaths were directly related to issues with the victim’s mental health or substance-induced disruptive behaviors.” NAMI found that people in a mental health crisis are more likely to encounter the police than get medical attention.

Deinstitutionalization

Defunding policing organizations to build up mental health and social service needs is a fallacy. Such short-sighted responses fail to address government responsibility to adequately fund all critical services. Robbing Peter to pay Paul has seen crime rise when police resources are reduced. This is a reactionary measure to poor decision-making and systemic lack of funding for the mentally ill that dates to the 1960s. This leads to the question: Why?

Deinstitutionalization was the idea that scores of mentally ill people could be released from mental health wards and given prescription drugs to manage their conditions. They would live productively in society, checking in at outpatient community mental health centers when experiencing crises or when their medications needed adjustment.

The 1963 Community Mental Health Act failed to channel federal grants to state and municipal governments to establish community mental health centers to deal with outpatient treatment of the mentally ill. Where are these resources? Where did the money go?

Through underfunding and mismanagement, the outpatient community mental health centers never materialized. The rates of the homeless mentally ill have skyrocketed, and jails and prisons that are often at capacity have become the new psych units.

The mental health care system has become increasingly fragmented, with each state developing its own legal process to detain or hold individuals in mental crisis. Some focus on hospital ERs being the entry point for evaluation and care; others involve a police hold and a ride to an inpatient, usually state-run mental institution. Today, many states have a waiting list for an open bed in a state facility.

The very legal system that shut asylums and state mental hospitals to protect patient rights is allowing individuals to wallow on the street in filth, with little chance for mental health care.

Today

People with mental illnesses are cycled through what police, mental health officials and advocates agree is a dizzying, revolving door of temporary psychiatric units and jail wards, never getting the long-term care they need before they are pushed back onto the street.

NAMI estimates that 25% to 40% of the mentally ill today will encounter the criminal justice system for one reason or another. Studies indicate that up to 20% of calls to law enforcement have a mental health connection, and people with mental illnesses are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter.

“The bottom line is that the mental health systems in this country, and this state and this county, are completely inadequate,” said Dr. Jonathan Sherin, Los Angeles County’s director of mental health, according to the Los Angeles Times. “We have what I call the open-air asylum of the street, and the closed-air asylum of the jail.”

Crisis intervention team (CIT) training: An answer?

CIT training consists of a 40-hour course dealing with mental health crises. CIT only deals with the crisis of the moment, not the need for resources once the individual is taken into custody for a mental health evaluation. CIT is a reasonable response to the reality that the mentally ill will likely remain heavily involved with the criminal justice system for the time being.

Some form of CIT is in use in places where approximately half the U.S. population lives, though the quality and nature of these programs varies widely. Yet, cities and counties often fail to carefully integrate the program into the wider mental health care system by routing calls away from police. CIT can’t take the place of proper treatment. Its popularity shouldn’t divert resources or attention from genuine mental health care reform.

Alternative response: fire departments, EMS and mental health?

Without guns or a focus on punitive action, fire departments should be better suited than law enforcement to respond to mental health crises. Mental health issues are more closely associated with an aid call than a crime response.

According to the Albany Law School, a national poll found that 70% of likely voters support a non-police response for 9-1-1 calls involving mental health crises, and 68% support the creation of non-police emergency response programs.

This philosophy represents one of many approaches that communities are taking to better protect those with serious mental illness. This approach is needed given the high rates at which those with diagnosed (and often undiagnosed) mental illness suffer injury, arrest or death at the hands of the police.

This is not to say law enforcement shouldn’t respond to mental health emergencies. With training and close partnerships with mental health professionals, law enforcement officers can work as a team to defuse tense standoffs and hand off individuals to a mental health crisis team for further evaluation and stabilization.

A crisis team approach like Crisis Assistance Helping Out on Our Streets (CAHOOTS), founded in 1989 in Eugene, Oregon, is a model that many communities have looked to for guidance in developing their own programs. When a call involving a mental health crisis comes into the CAHOOTS non-emergency line, a medic and a trained mental health crisis worker are dispatched. If the call involves violence or medical emergencies, they involve law enforcement. In 2019 (the most recent year of published data), out of 24,000 CAHOOTS calls, mobile teams only requested police backup 311 times.

Other pilot programs and discussions to reduce police responses are active in major cities including San Francisco, Chicago, Denver, Portland, Austin, Albuquerque and Orlando. Other areas are evaluating their own EMS, fire and mental health response mix.

Law enforcement focuses on public safety, investigation and arrest. The mental health community is focused on restoring and protecting the safety of a patient in crisis. Law enforcement personnel, while trained in many aspects of human behavior, are not licensed mental health providers, and what they see and report to mental health professionals may not be interpreted in the same way.

A new multidisciplinary response to mental health crisis is needed. The police can no longer be viewed as the catchall service provider for every community crisis when such calls are more closely related to a medical emergency than a criminal event. Law enforcement leaders are frustrated and look forward to identifying solutions that balance the collective good of individual rights and connecting people in crisis with the appropriate caregivers.

As seen in the January 2022 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: