The “dark web” is a term shrouded in both mystique and intrigue. Becoming ingrained in our culture since the reports were published highlighting the infamous “Silk Road” in 2013, it is safe to say that what we know as the dark web has become part of the internet experience today.

The “dark web” is a term shrouded in both mystique and intrigue. Becoming ingrained in our culture since the reports were published highlighting the infamous “Silk Road” in 2013, it is safe to say that what we know as the dark web has become part of the internet experience today.

For law enforcement, there has been a widening gap between state, local and tribal partners (SLTT) and federal entities when it comes to understanding and investigating cases that have a nexus to the dark web. Often disenfranchised by the complexities involved, SLTT partners have adopted the preconceived notions that cases involving the dark web are beyond their purview and that only cases conducted under auspices of the FBI, HSI, DEA, etc., are successful.

In training environments, there’s a question that often comes up: “What exactly is the dark web?” The preconceived notions that exist about the dark web in pop culture transcend to law enforcement — the belief that it’s the “untraceable internet” dedicated to contraband and the darkest desires of the human mind.

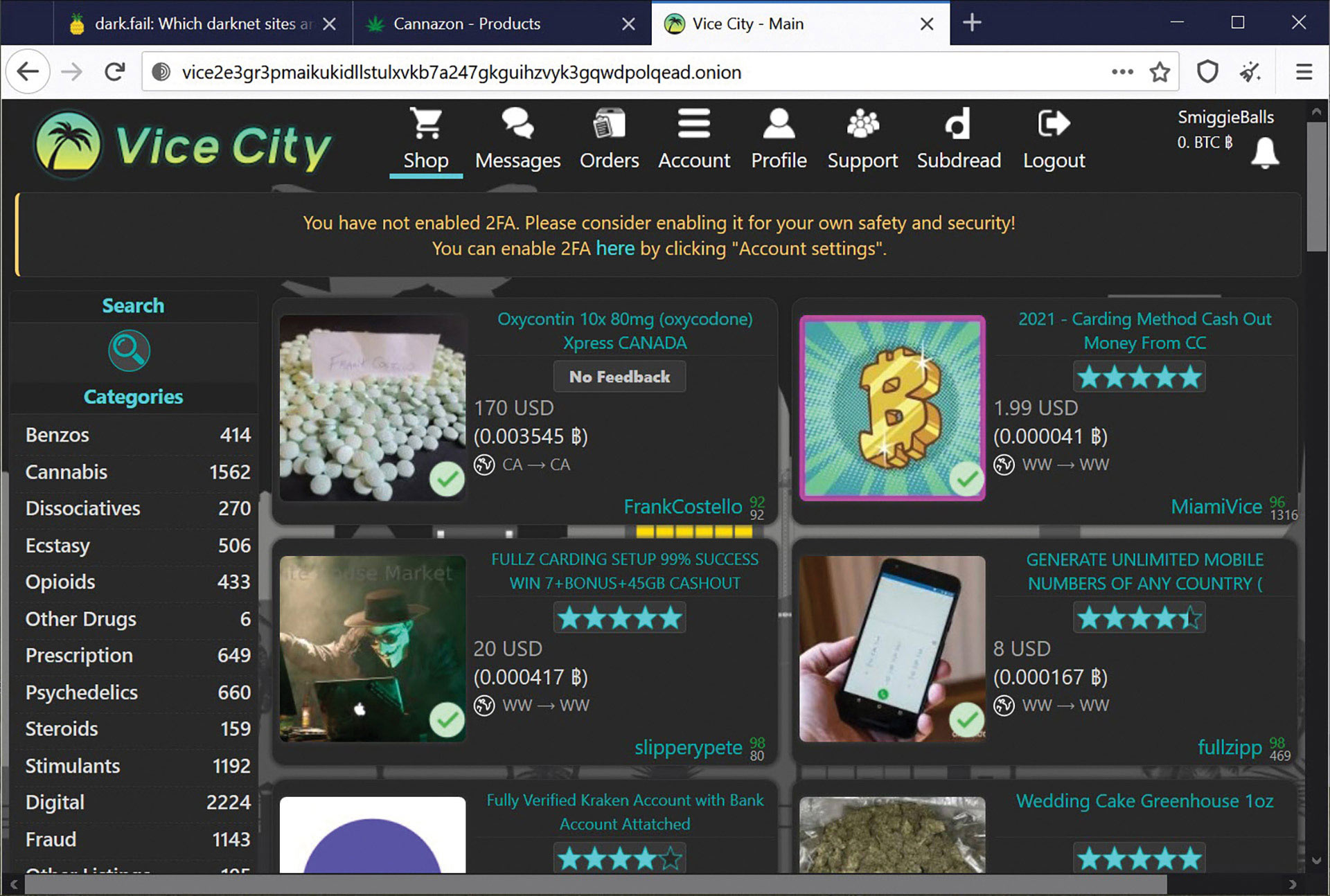

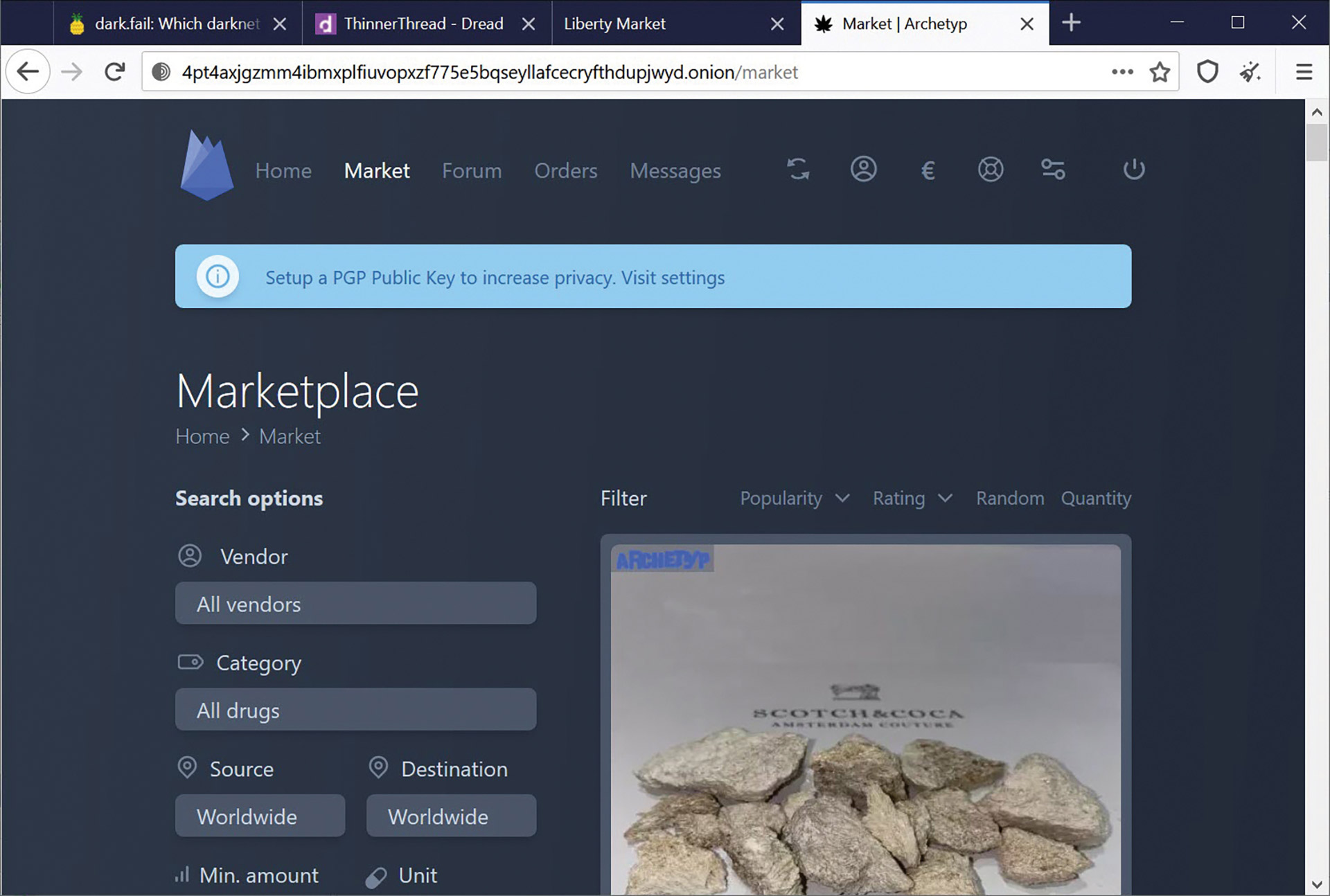

With such shows as Mr. Robot and movies like Unfriended: Dark Web furthering that narrative, it is safe to say that when the average person is asked about the dark web, they associate the “Silk Road” and the markets dedicated to selling drugs, guns, trafficked humans, murder for hire and child exploitation. While these associations are not unwarranted, much has evolved over the past eight years pertaining to the dark web. First and foremost, the dark web consists of unindexed content on various “darknets” delineated by how the sites are hosted and the software required to access them. According to recent statistics concerning the content of the entire world wide web, the darknets make up less than 5%[1]G., D. (2022). “How Much of the Internet is the Dark Web in 2022?” tinyurl.com/yycb4avm. of the content of the internet. So, what are these darknets?

When it comes to law enforcement’s familiarity with the dark web, I will espouse that there has been an enormous disconnect.

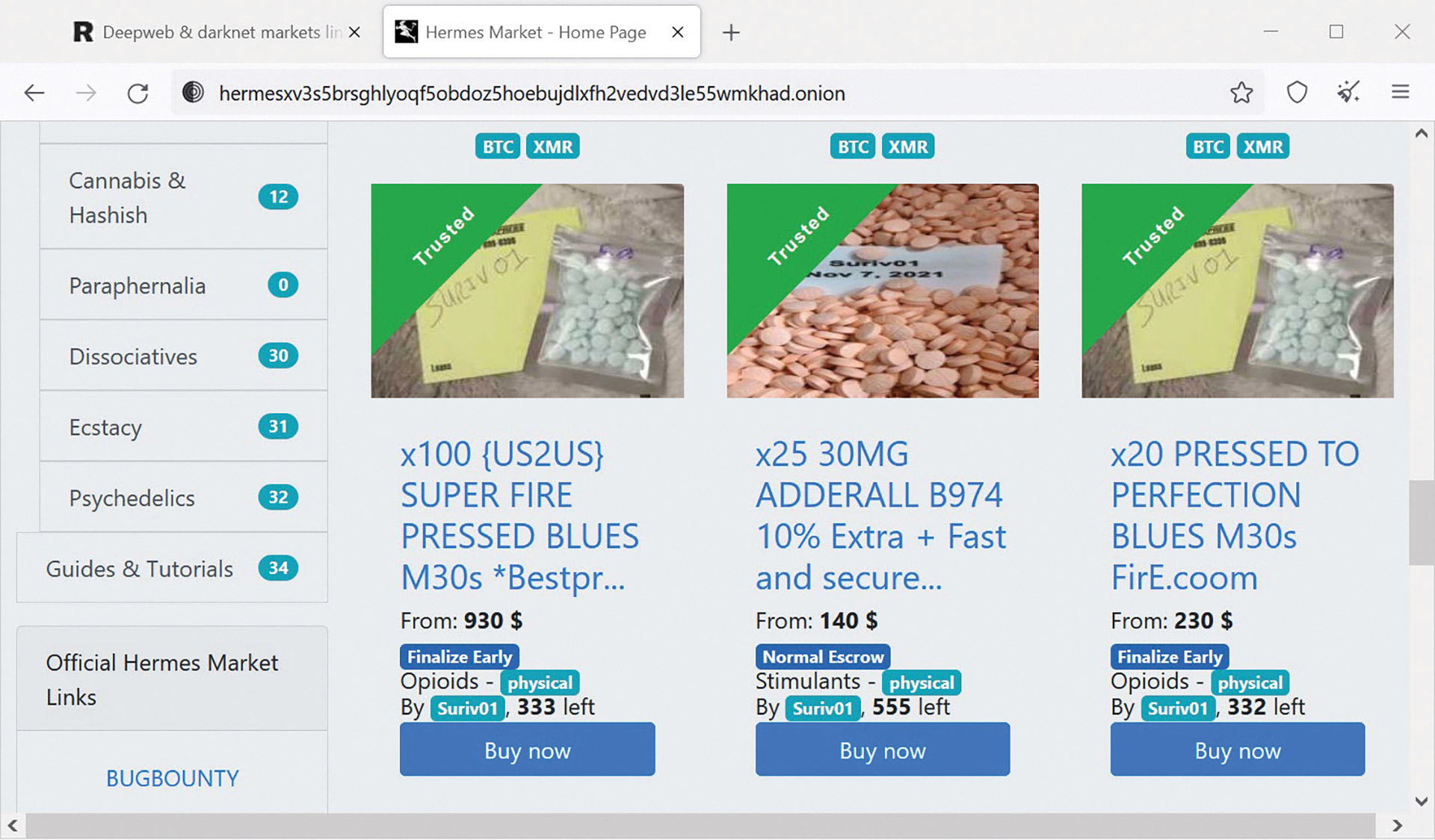

As of late 2021 into early 2022, there are over two million users of The Onion Router (TOR) network daily (tinyurl.com/yc2vvcw2). The TOR darknet is the most stable and undoubtedly most popular. On average, the United States accounts for over 20% of the traffic on the TOR network (tinyurl.com/4af2j5hc). While these metrics can be obfuscated by VPN usage, it is a safe assessment that the United States likely has the highest percentage of TOR users in the world. These statistics coincide with a 2020 report that dark web activity has increased 300% since 2017.[2]Nalapat, S. (2020). “Dark web activity has spiked over 300 percent since 2017: What’s driving boom in the internet’s underbelly?” tinyurl.com/3jr9yjnr. The notorious darknet markets, like the Silk Road (tinyurl.com/ynd7wrsx), AlphaBay (tinyurl.com/yc7v452w), Wall Street Market (tinyurl.com/2p9fj2sd), etc., have all been hosted on the TOR network due to the darknet’s stability, ease of use and popularity. However, TOR is not the only darknet. Arguably, the second-largest darknet is the Invisible Internet Project (I2P). With an estimated 35,000 users daily (tinyurl.com/mrxw2tjv),

I2P’s popularity continues to rise. In the same breath, I would be remiss not to mention the growing darknets of ZeroNet and GNUnet. It is safe to say that each day, what we know as the dark web expands. However, it must be understood that not everybody on these darknets is up to something criminal.

When it comes to law enforcement’s familiarity with the dark web, I will espouse that there has been an enormous disconnect. With proper training scarcely available to SLTT partners concerning how to investigate cases with a nexus to the dark web, specifically narcotics, it’s no wonder why the belief that those types of cases can only be handled by federal partners is so prevalent. As an investigator who has had the distinct privilege of serving on two separate federal task forces combating the contraband and illicit markets of the dark web, I saw the extreme detriment to this mindset.

Between April 2020 and April 2021, our nation saw the most overdose deaths in history.[3](2021). “Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually.” tinyurl.com/2hrhrab7. The surge in fentanyl (tinyurl.com/3ef6x5zm) has been the contributing factor to the harrowing overdose numbers, whereas more narcotics are laced with fentanyl than ever before.[4](2021). “Sharp Increase in Fake Prescription Pills Containing Fentanyl and Meth.” tinyurl.com/c43m4ev5. With no available data to determine how many of those overdose deaths were related to narcotics purchases from the dark web, what can be safely ascertained is the users of the dark web rose in tandem with the overdoses between 2020 and 2021.[5]Bracci, A., et. al. (2021). “Dark Web Marketplaces and COVID-19: Before the Vaccine.” tinyurl.com/yc4st8hv. This begs the question: Is the lack of data on overdose deaths related to dark web purchases a symptom of the much larger problem of lack of investigations into overdose deaths to begin with?

In my tenure with the Drug Enforcement Administration, I saw firsthand how overdose deaths related to dark web-sourced narcotics were seldomly investigated on the SLTT level. While these circumstances aren’t derived from one singular problem, the consensus I determined was the lack of a proper outlet to provide this information specific to the dark web. For example, if a local police department determined an overdose death to be caused by narcotics purchased off the dark web, that information wouldn’t go beyond that department. The overdose death information was forwarded to the overseeing Drug Monitoring Initiative (DMI), but any further criminal investigation was unlikely.

The deconfliction systems that currently exist, commonly conducted under the overseeing High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA), often leave SLTT partners out of the investigatory process. Without having direct access to those deconfliction systems, the SLTT partners often don’t utilize them. As such, this results in either a “stovepiping” of intelligence that disenfranchises the SLTT partners or a lack of intelligence altogether.

I founded the Ubivis Project as a way for SLTT partners and the general public to report the vendors of narcotics on the dark web. For the general public, they can remain as anonymous as they want to be. For SLTT partners, all that is necessary is to know the specific vendor’s moniker and provide a department case number with contact information, specifically a phone number and email. If a fatal or nonfatal overdose is related to a submitted vendor, the information input to the Ubivis Project populates on the “Overdose Crisis” map (tinyurl.com/2p84j86y). This is viewable to anybody and merely shows the moniker/vendor name attributed to the reported overdose geolocated from the submitted information. All reports submitted to the Ubivis Project are vetted and forwarded to federal partners as a way to keep SLTT partners involved in the process. Currently, there is a searchable repository being developed where members of the Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal (LEEP) will be able to register for access to readily search monikers/vendors. Users will be able to see associated submitted cases, as well as associated queries by other users when searched.

“Ubivis” is Latin for everywhere, and that is what is needed to aptly address the ongoing plague of dark web-sourced narcotics flooding our communities and causing overdoses. It is a necessary, and quite frankly, overdue, investigatory avenue that only requests SLTT partners to provide minimal information to help correlate overdoses related to dark web vendors.

As seen in the April 2022 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below:

References

| 1 | G., D. (2022). “How Much of the Internet is the Dark Web in 2022?” tinyurl.com/yycb4avm. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Nalapat, S. (2020). “Dark web activity has spiked over 300 percent since 2017: What’s driving boom in the internet’s underbelly?” tinyurl.com/3jr9yjnr. |

| 3 | (2021). “Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually.” tinyurl.com/2hrhrab7. |

| 4 | (2021). “Sharp Increase in Fake Prescription Pills Containing Fentanyl and Meth.” tinyurl.com/c43m4ev5. |

| 5 | Bracci, A., et. al. (2021). “Dark Web Marketplaces and COVID-19: Before the Vaccine.” tinyurl.com/yc4st8hv. |