On average, nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner. This equates to more than 10 million abused women and men each year. Often viewed as one of the most dangerous of law enforcement activities is responding to the domestic violence (DV) call. FBI statistics show an average of 4,194 officer assaults occur annually from DV calls. Over the past decade, more than 500 officers nationwide were murdered at a DV scene.

The American Journal of Emergency Medicine reports that DV cases increased by 25% to 33% globally in 2020. The National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice shows an increase in cases in the U.S. by a little over 8.1%, following the imposition of lockdown orders during 2020. The severity of physical violence was 1.8 times greater.

The holiday season is always a busy time for folks in emergency services, police, fire and paramedics. Unfortunately, while the holidays are a joyful period sprinkled with many family and social events, this same period routinely spikes with increases of DV, assaults, suicides, thefts, burglaries and vehicle crashes, and that list seems to grow a little every year.

Policing must approach domestic violence calls with empathy and thorough investigations.

Whether because of the built-up stress of the season, confined togetherness, dreary winter weather or increased stress generated by a struggling economy, police agencies will be first on the scene for a busy season.

DV usually occurs in a domestic space when one individual holds power over another. According to the CDC, approximately one in four women and one in 10 men report experiencing some form of intimate partner violence each year.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), stay-at-home orders may cause a catastrophic milieu for individuals whose lives are plagued by DV.

The NIH collected data from U.S. police departments that provided insight into the effects that COVID-19 had on DV in some regions. For instance:

- Portland, Oregon, public schools closed on March 16, 2020, and stay-at-home orders started on March 23, 2020. Following these events, the Portland Police Bureau recorded a 22% increase in arrests related to DV compared to prior weeks.

- San Antonio, Texas, schools closed on March 20, 2020, and stay-at-home orders started on March 24, 2020. The San Antonio Police Department received an 18% increase in calls pertaining to family violence in March 2020 compared to March 2019.

- The Jefferson County, Alabama, Sheriff’s Office reported a 27% increase in DV calls during March 2020 compared to March 2019.

- New York City schools closed on March 16, 2020, and stay-at-home orders started on March 22, 2020. During the month of March, the New York City Police Department responded to a 10% increase in DV reports compared to March 2019.

The American Journal of Emergency Medicine reported alarming trends in U.S. DV cases, and the National Domestic Violence Hotline (NDVH) received more than 74,000 calls in February of 2020, the highest monthly contact volume of its 25-year history.

The rise in DV during COVID was not limited to the U.S. The United Nations called the situation a “shadow pandemic” in a 2021 report about DV in 13 nations in Africa, Asia, South America, Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

Victims fear police

Whether this upward trend in violence continues is not yet known. But police response to DV continues to fall short in the eyes of many victims. In a 2021 survey conducted by the NDVH, survivors of violence feared that contacting police would make things worse, might result in their arrest or loss of custody of their children.

The survey highlighted the main reason domestic abuse victims reach out to law enforcement is because there is no other alternative. This is an opportunity for law enforcement to use community policing to look beyond the criminal justice system for responses. There must be a way to meet survivors’ needs for justice and safety, including social services, mental health supports, community interventions, housing resources, financial assistance and more, by bringing together other services to deal with DV.

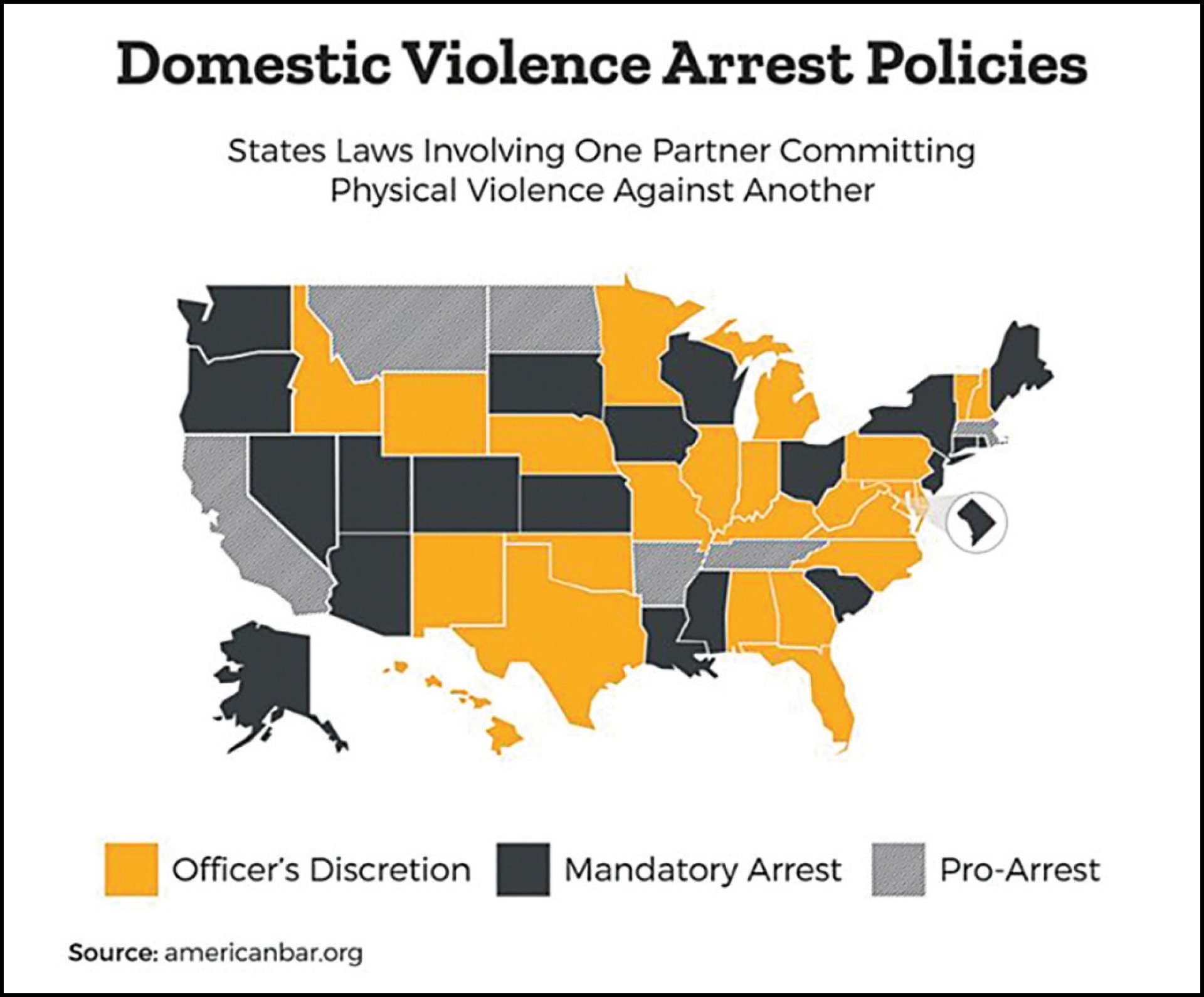

Since the 1980s, many states have passed different arrest laws to combat DV. A mandatory arrest law requires that a person be arrested at the scene of a domestic disturbance, while discretionary arrest laws allow for, but do not mandate, a warrantless arrest. Preferred arrest laws promote arrest as a response, but also do not mandate its use.

Fewer than half the states have mandatory arrest laws. These were designed to focus on victim safety, separating the victim from their abuser, and to help set the wheels in motion to mandate abuser accountability.

Police response

We know that DV impacts the entire family, and that family violence can become generational. You can become a lifesaver. DV calls can be frustrating, but replace that frustration with being thorough in your investigation. Be tenacious. Detailed reporting of your observations is critical in building a case for prosecution, as the first step in evaluating resources.

Every community across the country has a continuum of resources ranging from multiple helping agencies to minimal support.

The NDVH survey reported that of those who called the police, 55% believed they were discriminated against in some way by the police; of those who called the police, 25% were threatened with arrest; and 92% of victims who had not called the police were very or somewhat afraid about how the police would react. Further, when asked if other resources had been available, would the survivors have chosen an alternative over police, 71% answered “yes.”

Policing must approach DV with empathy and thorough investigations. If the victim were our own brother, sister, son or daughter, we would expect a top-notch investigative effort. But not every victim is going to be cooperative. Some victims will not want to see an arrest made or prosecution occur, even if that would be the first step in breaking the cycle of violence.

In recent years, evidence-based prosecutions have caught on in the police response to incidents. These are investigations that are strong enough for prosecution without the benefit of victim cooperation. This road map to success includes:

- Complete documentation of initial observations

- Detailing the crime scene environment

- Documenting suspect and victim statements

- Gathering hearsay information

- Collecting and photographing physical evidence

- Looking for common DV injuries such as defense wounds in detail

- Identifying who the primary aggressor is

- Utilizing victim safety planning

DV cases and their investigation can be frustrating, fraught with high emotions and challenging to arrive at a successful and safe conclusion. It all starts with patrol response and the motivation to train harder, develop new helping agency partnerships and being tenacious in being a lifesaver.

The COPS Office’s Community Policing Dispatch e-newsletter has an article entitled “Domestic Violence 101: How Should a Law Enforcement Agency Respond?” The National Institute of Justice (NIJ) published a handy report available online titled “Practical Implications of Current Domestic Violence Research.” Google both these resources for innovative ideas.