One of the challenges for kindergarten to 12th grade (K–12) schools and their law enforcement partners is confusion regarding emergency management terms and procedures. Terms like shelter in place, secure campus, lockout and lockdown often get assigned the meaning. The problem is that these terms are related to a specific hazard or threat, eliciting a very different response. The purpose of this article is to bring clarity to these terms and shed light on current best practices for officers supporting K–12 schools in developing their emergency

operations plans.

Environmental hazards or human hazards?

Emergency response protocols can be broken down into two hazard categories: environmental hazards and human hazards or threats. Environmental hazards impact our surroundings and can be natural or manmade. Environmental hazards are most commonly associated with natural disasters, such as tornados, earthquakes, wildfires, floods and avalanches. Environmental hazards can also include severe weather patterns like lightning, hail, heavy winds or poor air quality. Animals or insects can also be categorized under environmental hazards. Manmade environmental hazards could include a gas leak, downed powerlines or airborne contaminants created by the release of hazardous materials.

Human hazards, or threats, are events that are driven by an individual’s actions. A human hazard is an event where there is a likely potential for emotional, psychological, and/or physical harm to stakeholders. However, the intent of the individual driving the event is not to cause harm. Potential harm to stakeholders is simply a byproduct of being exposed to the incident. Examples would be exposure to a traumatic event, such as a deadly car crash, a student flipping desks or an irate parent swearing at a staff member. Human threats are incidents where the actions of an individual are intended to cause emotional, psychological and/or physical harm to stakeholders. Human threats are directed and targeted attacks against schools, staff or students.

Now that we have a baseline for the hazard categories, let’s define common emergency response terms.

Evacuation

“Evacuation” is used for an environmental hazard inside a building that makes the building unsafe to be occupied. Examples of hazards that may require an evacuation response are fires, gas leaks, flooding or a loss of structural integrity. Evacuations are controlled and deliberate. The primary actions for staff are to move students outside the building to a designated on-site evacuation point and report attendance to administrators.

Shelter in place

“Shelter in place” is used for an environmental hazard, outside buildings, on or off campus, making the area unsafe to be occupied. Examples that may require a shelter-in-place response include a tornado, heavy smoke from a nearby fire, lightning, a swarm of bees or a dangerous animal (such as a coyote) on campus. Actions taken by staff will be dependent on the imminence and severity of the hazard. Imminent hazards may require staff and students to seek the nearest structure for shelter, such as a dugout during a thunderstorm. In most cases, stakeholders will move inside of buildings, and instruction will continue as normal. Administrators will determine if movement outside of buildings will be limited or prohibited altogether. Some organizations will use the term “reverse evacuation” instead of shelter in place, although this phrase is outdated and not in alignment with current best practices.

Hall check

“Hall check” is used for a human hazard on campus. A hall check is used to clear the halls or the area surrounding an incident. The purpose of a hall check is to limit students’ and staff’s exposure to an event. In most cases, a hall check is used when a student is having an uncontrolled outburst, or there is a medical emergency, such as a student having a seizure. Staff will clear the halls, keep students in classrooms, and continue teaching. “Hold” is another term used with the same purpose as a hall check.

Secure campus

“Secure campus” is used for a human hazard or potential threat, on or off campus. The most common potential threats to initiate a secure campus response are police activity near a school, an unidentified individual on campus or a non-custodial parent trying to make contact with a child. Some districts, recognizing the overlap with other protocols, will also use secure campus in the same manner as a hall check. Staff will ensure exterior entryways are locked and secure, move students to their designated classrooms, lock and close classroom doors, and continue teaching. Movement outside of buildings is not authorized, and movement inside buildings is at the discretion of school administrators.

Some districts are still using the term “lockout” for “secure campus,” also referred to as “secure” by other organizations. It is critical to note the term lockout should not be used, as it is too similar to “lockdown” and creates confusion. This confusion was highlighted in the Rigby Report (tinyurl.com/2p86ke8p) following the 2021 shooting at Rigby Middle School in Rigby, Idaho.

Additionally, the I Love U Guys Foundation (tinyurl.com/2aynt975), which created the Stand Response Protocol, adjusted its language from “lockout” to “secure” following the Rigby active shooter incident.

Lockdown

“Lockdown” is used when there is a human threat on campus that is actively harming or attempting to harm stakeholders. Lockdown is a single-option response, where stakeholders are trained to create a safe space and prevent an assailant from gaining access to victims. While lockdown is the terminology and protocol used by the overwhelming majority of school districts, a lockdown-only approach is not aligned to emergent research or best practices.

Since 2013, the U.S. Department of Education, in collaboration with multiple federal agencies, stated that training schools in a single response for an active-shooter incident are not enough. Given the dynamic nature of active-killer events, staff and students must be taught and prepared to exploit whatever options are best for

their safety,

Options-based response

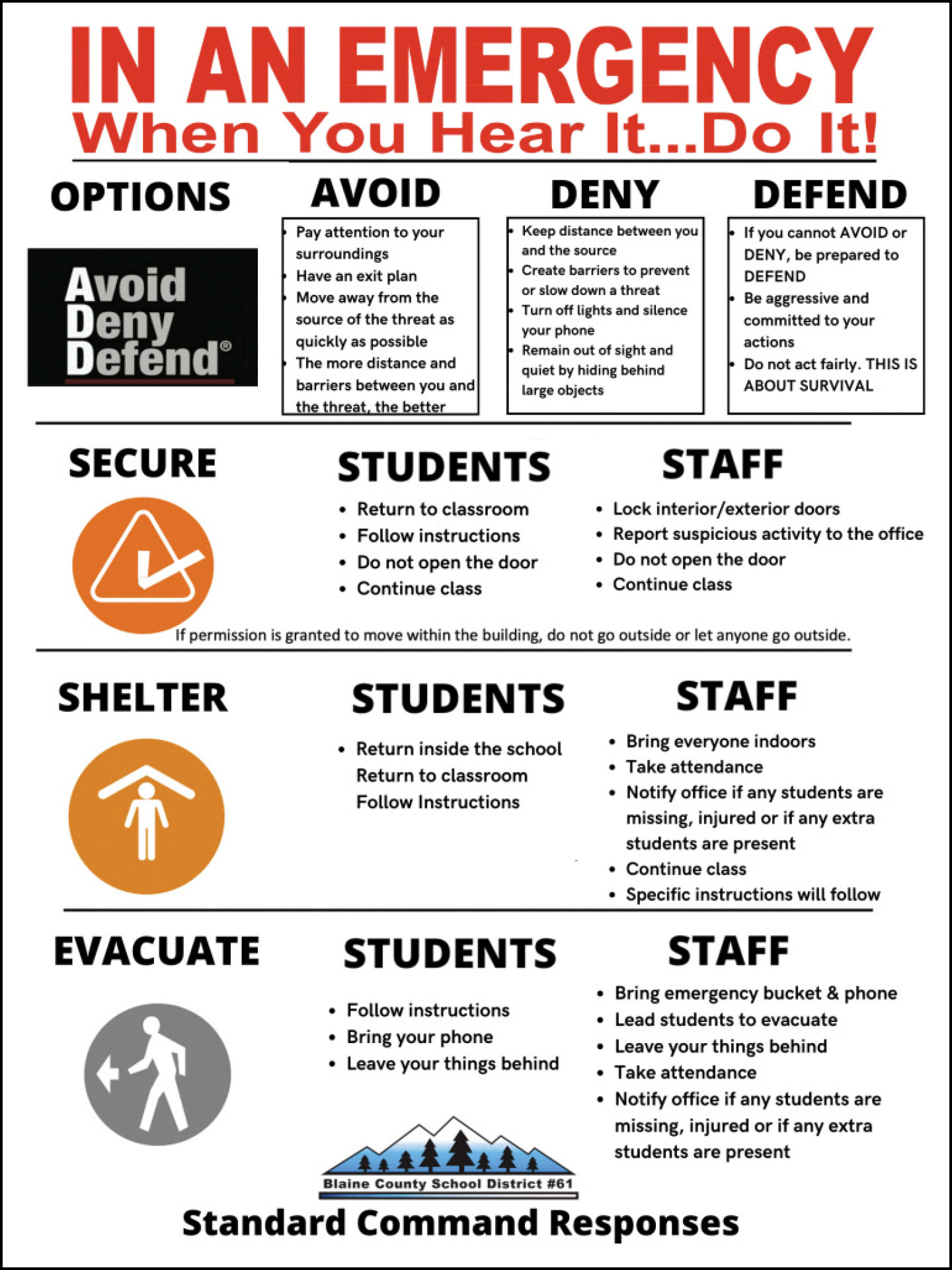

An options-based response, or multi-option response, is the system aligned to best practices and emergent research when preparing K–12 schools for an active threat. A multi-option response is a fluid response system whereby users select which option is best for their safety. A fluid system means users can adjust from one option to another based on available information or new conditions. The most popular options-based systems include “Run, Hide, Fight”, ALICE and “Avoid, Deny, Defend.”

Standardized protocols and communications

Standardize procedures and communications are the foundation for developing emergency response protocols. Law enforcement supporting K–12 schools should become familiar with these terms in order to better prepare staff and students for an emergency. Words have meanings. Confusion over terms and the actions taken by staff in a crisis can create costly delays or unnecessary reactions.

As a school resource officer and emergency manager, I have experienced firsthand the negative consequences of having emergency protocols that are unclear and not aligned with best practices.

Parents and teachers panicking because they thought they were in lockdown when they should have been in secure campus. Staff bringing students back into a building with a potential shooter because they were only taught a single response rather than given the authority to escape campus. Schools rely on the guidance of law enforcement officers to support them in developing evidence-based emergency response protocols. My hope is this article will bring clarity to common terminology and support officers in keeping our staff and students safe.

As seen in the November 2022 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: