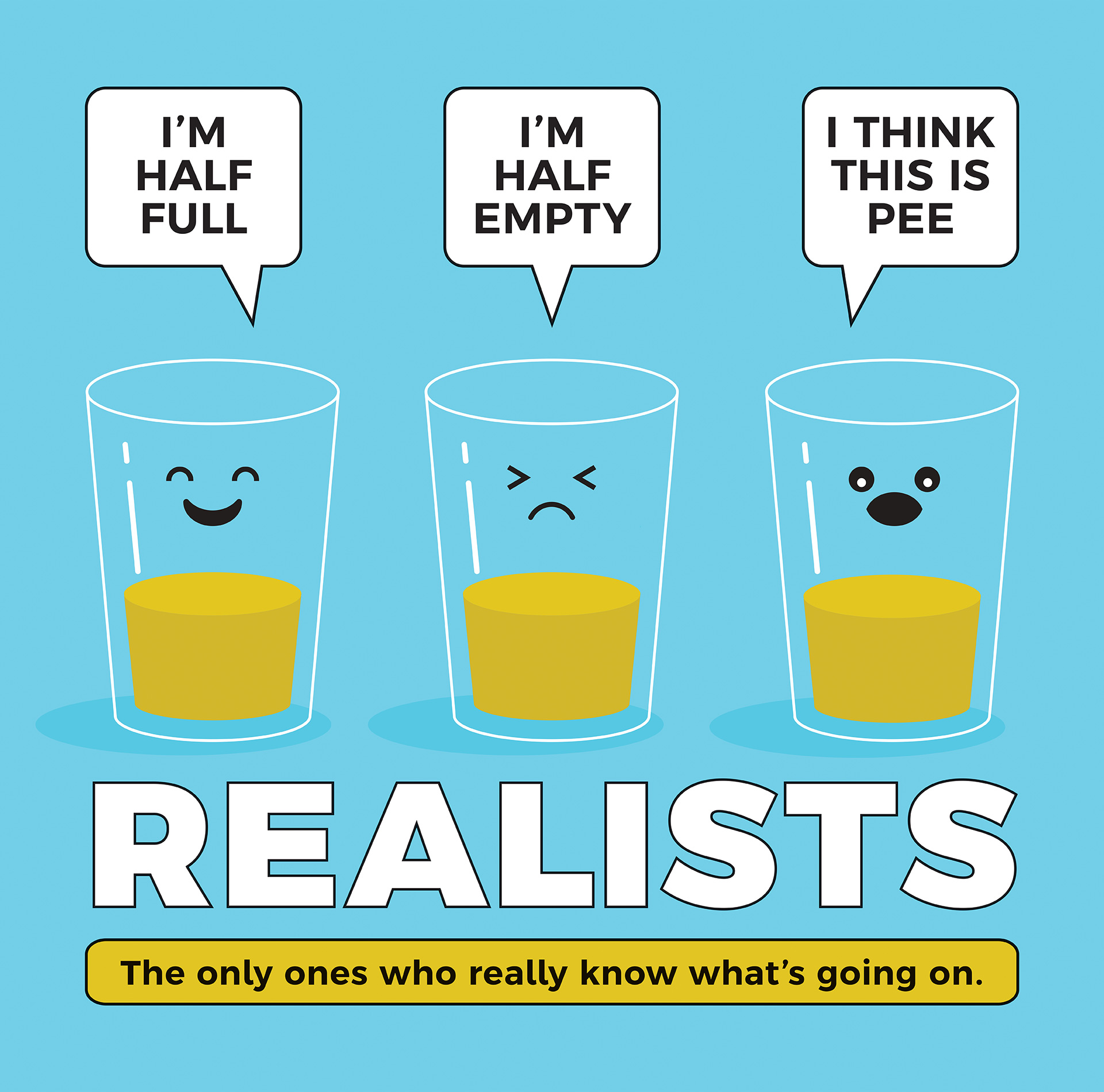

A psychologist, by definition, is a doctor (Ph.D. or Psy.D.) who studies the mind, emotions, cognition, social processes and human behavior. Within the field of psychology, there are different specializations, including child and adolescent, forensic, research, police and public safety, and others. Similar to your motors, detectives and community service officers, there is a baseline understanding of the job, with additional training and positions for persons who choose a specialty. I am a police psychologist, and by definition, police psychologists have the mission of assisting law enforcement in carrying out their objectives with optimal effectiveness, safety and health while utilizing evidence-based practices and ensuring conformity to laws and ethics. The primary domains under which police psychologists operate are clinical intervention (therapy, critical incident stress debriefs), assessment (pre-employment, fitness for duty), operational support (crisis negotiations, behavioral threat assessment) and organizational consultation (innovative programs, data collection). Ultimately, the difference between a “regular” psychologist and a police psychologist is nicely summarized by the image on this page.

Some law enforcement organizations are embedding psychologists to assist in an operational capacity. The idea of bringing embedded psychologists alongside law enforcement in this way is not entirely new (LAPD’s Behavioral Sciences Services was started in 1968, for example) but remains novel. With a present and somewhat feverish focus on topics such as de-escalation, crisis intervention training (CIT) and officer wellness, perhaps the concept will be less novel in the coming years. Police psychologists can bring immense value to an organization beyond the typical contract for pre-employment and fitness-for-duty evaluations. Below are some examples of what this could look like.

Clinical intervention

Therapy: Police psychologists understand the unique stressors associated with the job, where most other psychologists don’t have the training or experience. It makes a difference when you walk into a therapist’s office and hear them say, “I know what you are dealing with, I have seen this before. You are not crazy. You are not alone, and I can help.” What most officers want is to feel better, and trust is hard to come by. By the time an officer makes the call to a psychologist for help, they probably have reached some breaking point or some new and awful low. We don’t have the luxury of time to waste — we need to connect the officer in need with the right care immediately to give that officer the best chance of being better, at work and at home. The cultural competency of the practitioner is going to make or break the intervention.

Critical incident stress debriefs (CISDs): A CISD is a semi-structured group intervention, led by a psychologist, that assists in the psychological and emotional processing of a traumatic incident. A CISD is designed to mitigate the impact of the stress response, assist in the ability of the individuals affected to go back to work and identify those who may need added support. Again, the key to a successful intervention is the cultural competency of the therapist. You don’t want to invite a clinician into a debrief who talks about how the only way to be successful in police work is to sleep eight hours a day, eat granola, do CrossFit and meditate daily. What an officer will hear is, “Health and wellness is out of reach for you. Don’t even bother trying.”

Assessment

Pre-employment/fitness for duty (FFD): Having your pre-employment and FFD psychologist is necessary and a huge asset to the field of policing and the community; however, having psychologists work with law enforcement in this way, and only in this way, has been damaging to the relationship between the two disciplines. For many cops, pre-employment evaluations are the first and only exposure to a psychologist they’ve had, and thus they are hesitant to reach out later in their careers. They hold on to the perception that it’s the job of a psychologist to determine whether or not they can still carry a badge and a gun. What I would invite you to consider is that your pre-employment and FFD psychologist should not also be the psychologist you use for wellness and other operations within the agency. Keeping the two separate helps facilitate trust and efficacy of the interventions

being offered.

Operational support

Crisis negotiations: SWAT and crisis negotiation team (CNT) callouts often involve a person in a mental or behavioral health crisis. For this reason, it’s helpful to have a psychologist who deploys with the negotiations team to assist in gathering intel, assessing the subjects’ behaviors and mental state, and advising the team on potential hooks, triggers and barriers. Not unlike cops, psychologists are trained to understand, predict and change behavior. What a psychologist can bring to the table is another set of eyes that sees problems through a different lens, based on varied training and experience, and can guide the team toward a successful disposition. Also, it wouldn’t hurt to put “consulted with the police psychologist” in the report.

Behavioral threat assessment: The best practice for navigating threats of targeted violence is to have a multidisciplinary team of subject-matter experts who have some awareness, involvement or influence with the person of concern. It’s helpful to have a psychologist comment on the impact a psychiatric disorder or symptom may have on behavior, as well as evaluate the mental and emotional aspects of the person of concern as the team develops their action plan. Additionally, it is not uncommon that in these cases, the threshold for criminal threats is not met, and thus it may be the psychiatric system of care (involuntarily hospitalization) that is needed to mitigate the potential for violence. Police psychologists can articulate the need and information in a way that will help improve the chances of the person being held, if that’s what needs to happen.

Organizational consultation

Innovative programs/data collection: The LE equivalent to the adage “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” might be “If all you have are cops, everything looks like someone else’s problem.” Our nation (generally speaking) is going through quite a mental health challenge. With drug use and mental illness on the rise and a concurrent steady decline of mental health providers and services, law enforcement is often left picking up the pieces. There is an enormous amount of funding being thrown at mental health programs and diversion initiatives, and in order to be competitive in the race to acquire the grant funds, agencies need to be able to succinctly state the problem and back it up with evidence. That can be a big task for small agencies or agencies with insufficient staffing. A police psychologist can assist with improving how an agency collects information on mental health calls, write grant proposals and attend high-level meetings where resource allocation is being discussed. It is helpful to have a subject-matter expert on your side in this fight to advocate on behalf of law enforcement and the community

they serve.

This is by no means a comprehensive list (we haven’t even spoken about depositions for use-of-force cases!). My hope is that we continue to build on the ways police psychologists can support law enforcement, the law enforcement mission and the men and women who wear the badge and do the work. (And if you’re still wondering, the answer is, it’s pee.)

As seen in the March 2024 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: