This shouldn’t shock anyone, but we live in a society that is reliant on ever-expanding technology. With technological advancements come new ways for criminals to take advantage of unsuspecting victims, as well as new ways law enforcement must fight those crimes. The effort to help cops in that battle has been led by three mobile apps — Nextdoor, Tango Tango and Clearview AI.

Nextdoor began in 2011 as a social networking service that allowed members of a community to get in touch with each other. It required users to submit their real names and the street on which they lived, allowing them to instantly be connected to others who live near them. It could be used to prepare for upcoming events, ask for recommendations or discuss neighborhood improvements.

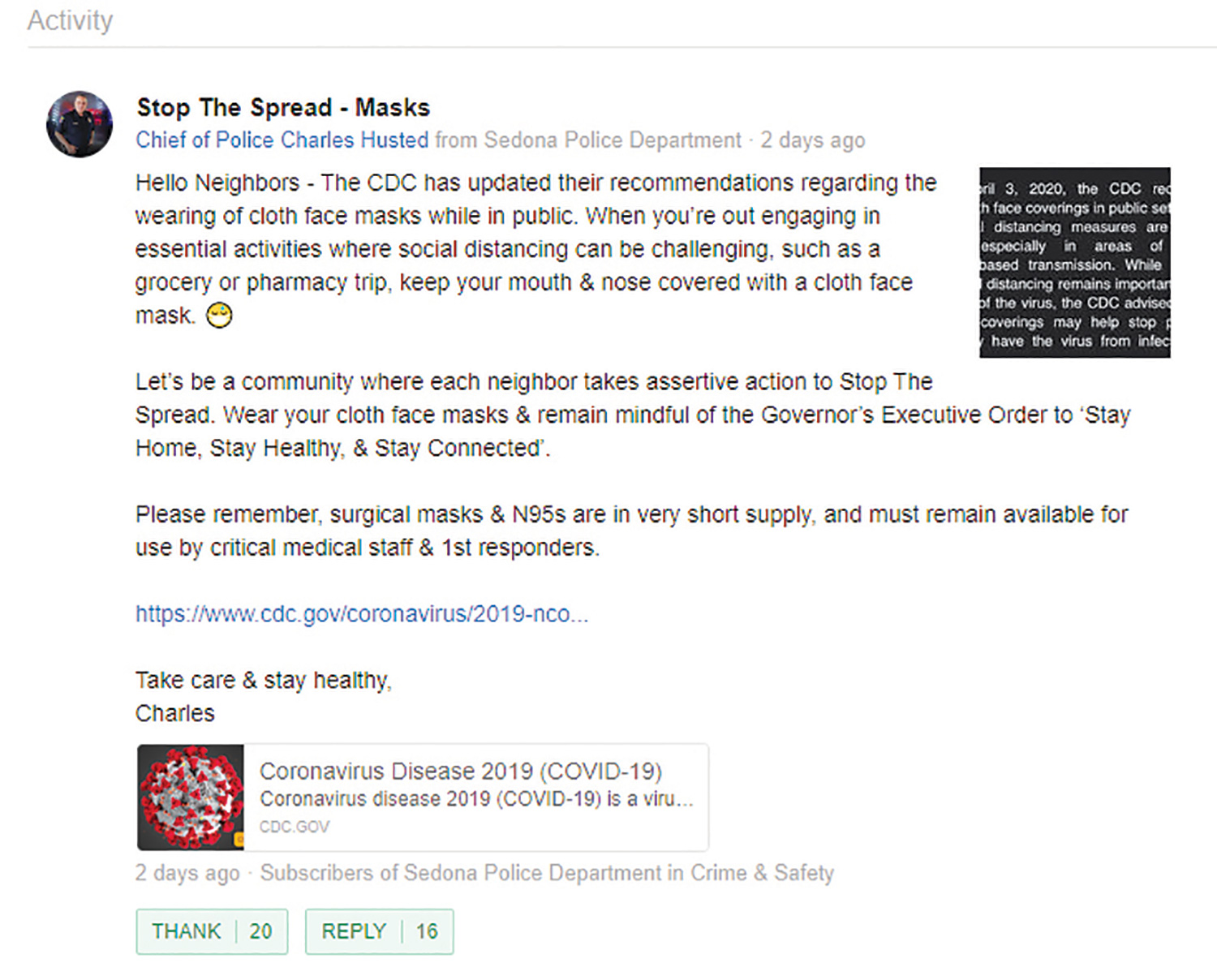

It was possible for law enforcement to use the existing app to connect with their community, but Nextdoor developers realized that agencies needed something more tailored to their needs. That led to the new Nextdoor for Public Agencies app, which launched in February. It allows police and fire departments, public schools, and City Hall agencies to keep local citizens updated, provide geo-targeted push alerts to specific neighborhoods and read their messages on the go.

“It allows the public agency folks to be in the field, be engaged in an incident and share info as quickly as needed,” Charles Husted, the police chief of Sedona, Arizona, told City Lab.

Husted, who previously served in the Sacramento P.D. before moving to Sedona, has been using the original Nextdoor app for years. It allowed him to have a personal relationship with the community and build trust. Last year, it enabled him to catch a criminal on a vandalism spree within 20 minutes, thanks to the quick circulation of the culprit’s photo. He’s something of a pro when it comes to Nextdoor, and he calls the new app a “game changer.”

Nextdoor has always tended to attract discussions about neighborhood happenings. Residents act as eyes on the street, giving updates about car break-ins, suspicious characters and other local threats. As time has gone on, Nextdoor has gotten better about directing those posts to the agencies that can use the information.

In 2016, it introduced a “Forward to Police” feature, which allowed users to send crime and public safety reports directly to law enforcement. If the “Forward to Police” feature indicated a concerted effort to work directly with law enforcement, Nextdoor’s new app is the natural evolution of that.

“Neighbors turn to Nextdoor every day to find trusted, relevant information about what’s happening where they live,” Nextdoor’s head of product, Tatyana Mamut, said in a statement. “Now, our agency partners can send information to their constituents with the tap of a button anywhere and anytime — even when they are away from their desk, after hours or in the field.”

Nextdoor is far from the only private tech company making a concerted effort to partner up with law enforcement. Where Nextdoor focuses on the connection between law enforcement and the community, Tango Tango focuses on the connection between law enforcement and other first responders. With the app, law enforcement can connect any smartphone to any radio channel, providing a wide coverage area and improving clarity.

Zach Tannett, the director of sales for Tango Tango, told WSFA-TV that the concept for the app came after 9/11, when first responders had difficulty getting in touch with each other.

“First responders in New York City could not talk to one another because they were on different radio systems and that created a huge problem, so there was a big push thereafter to make what people call interoperability a real thing,” Tannett said.

More than 100 public safety departments in Alabama have been using the app, and they’re loving it. Ernie Baggert is the Emergency Management Agency director in Autauga County, Alabama, and he has a glowing review.

“Some of our VHF radios are relatively weak in some of the areas, but we have a good, strong cell signal and so, because this does operate over the cell system, it’s an app that goes through those phones,” he said. “We actually have a lot better coverage now than we ever have had with the radios.”

Baggert said that the County used to struggle to communicate with nearby Chilton County over the radio, but since they’ve started using Tango Tango, they can communicate better and faster.

“This Tango Tango [app] is kind of like that translator,” he said. “It makes it to where everyone can talk together.”

While the initial impression of the app has been positive, there’s no expectation that it will completely replace radios anytime soon.

“We believe that at some point, probably within 10 to 15 years, there will be a shift that LTE-based services will take over from what’s called LMR, the land mobile radio, the traditional system that is in place now, but not until they have a more robust and dependable system,” Tannett said.

Tango Tango has existed for three years and is currently in use in more than 40 states. It can only be downloaded with special permission from the company, which helps make sure only the organizations that really need it are getting access.

While Nextdoor’s goal is boosting community engagement and Tango Tango’s goal is improving communication, Clearview AI is all about using facial recognition technology to catch criminals.

Clearview is one of several kinds of facial recognition software that have cropped up in recent years, but what sets it apart is its database. Typically, facial recognition software is sold to police and allows them to check law enforcement databases for images, which includes mugshots, driver’s licenses and sex offender registries.

However, that limits the selection of photos to people who are already in the system. What happens if a suspect has never committed a crime before and isn’t in the existing database? Then the software would be useless.

In contrast, Clearview searches through at least 2 billion photos that citizens upload to public websites like Facebook, Twitter and Venmo.

“Clearview’s speed and accuracy are unsurpassed. But the true ‘secret sauce’ is data,” Clearview wrote in a document sent to the Clearwater Police Department that was obtained by the Tampa Bay Times through a public records request.

It says the software has helped law enforcement with theft, bank fraud, child exploitation and countless other cases. It also touts that its algorithm has matching capabilities unrivaled by any other software and that it isn’t limited by the angle of the face in a photo like other recognition tools used by law enforcement.

“What Clearview is [doing] is taking facial recognition and putting it on steroids,” Pinellas County, Florida, Sheriff Bob Gualtieri said.

Clearview’s unparalleled database of images is starting to make it the go-to destination when law enforcement needs facial recognition. The Tampa Bay Times reported that in Florida alone, 12 different law enforcement agencies have tried out or bought access to the database.

Sergeant Nick Ferrara of the Gainesville, Florida, Police Department told the Tampa Bay Times that he’s used several other facial recognition programs, including one managed by the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office that is used by law enforcement throughout Florida. Pinellas started building that system nearly 20 years ago and it can access up to about 38 million images, including mugshots, driver’s license and ID card photos. But Ferrara said Clearview proved itself “clearly superior.”

The Gainesville P.D. signed a $10,000 contract with Clearview in September, and Ferrara now can search for faces across the country. He said he’s made “numerous identifications of suspects” with the technology, specifically citing shoplifting and financial fraud cases.

“I’m all about using tech to gain an advantage to catch bad guys,” Ferrara said.

That’s an attitude shared by many law enforcement officers, but it’s one that is receiving pushback from personal privacy advocates. They maintain that law enforcement using a database like the one Clearview maintains is a fundamental invasion of personal privacy.

“We sometimes talk about the slippery slope of government incursions on people’s rights,” Nathan Wessler, a staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union who focuses on surveillance and privacy, told the Tampa Bay Times. “The prospect of this kind of facial recognition in government hands is the bottom of that slope — it’s the place we don’t want to get to.”

The realization that Clearview has been pulling photos from public websites has led to pushback from those websites as well. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Venmo have all told the company to stop pulling information from their sites. New Jersey’s attorney general has said police in his state should stop using the software.

Privacy advocates have expressed similar problems with Nextdoor’s increasing integration with law enforcement. They say the partnership between the app and law enforcement leads to citizens writing amateur police reports that give skewed visions of the city in which they live, resulting in a cycle in which neighborhoods actually worsen because people already believed they were worsening.

Critics also say that distilling crime reporting down to a simple click of a mouse can escalate minor complaints that normally wouldn’t be deemed worthy of police involvement.

“I’m concerned about the general trend of these murky or opaque private-public partnerships with police or other core government services that were traditionally more publicly managed,” Rachel Thomas, the founding director of the Center for Applied Data Ethics at the University of San Francisco, told City Lab.

While no technology is perfect, these apps have certainly been able to help police serve and protect their local communities. As time goes on and these pieces of software become more tightly intertwined with law enforcement, they could provide cops with exactly the ammunition they need in their fight against crime.