School active shooter incidents are a unique phenomenon. When preparing for or responding to one of these horrific tragedies, officers should consider how their training and tactics should differentiate between these attacks and other active killer events. Here is what we have learned from two decades of school active shooter incidents and the implications for officers supporting local schools.

The FBI defines an active shooter as “one or more individuals actively engaged in killing or attempting to kill people in a populated area.” The FBI and the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) program have produced six reports from 2000 to 2020 outlining active shooter incidents in the United States. According to these reports, there have been 44 active shooter incidents (ASIs) on kindergarten to 12th grade (K-12) campuses in the U.S. during this time period.

Solo-officer tactics should take precedence over team techniques.

Location of events

Facts: Of the 44 attacks, 27 (61%) targeted high schools, eight (18%) occurred on junior high/middle school campuses, six (14%) happened at elementary

schools, two (5%) occurred at school board meetings and one (2%) took place at a pre-kindergarten to 12th grade school.

Implications: When allocating resources to prevent, protect, mitigate and respond to a targeted attack at an educational facility, schools and their law enforcement partners should prioritize sites based on historical data. High schools should be given priority, followed by junior high/middle schools, then elementary schools. When preparing stakeholders to respond to an active killer event, drills and training should be differentiated to the age and abilities of students with trauma-informed practices leading curriculum development.

Assailants’ affiliation to school

Facts: The 44 attacks were carried out by 45 assailants, with only one incident involving two suspects. Of those, 38 assailants (84%) were current or former students of the school being targeted. Three assailants (7%) had no connection to the site, two suspects (4.5%) were employees at the school and two attackers (4.5%) had a romantic connection to an employee.

Implications: The majority of assailants have a detailed understanding of the campus layout, security features and day-to-day operations of the targeted school. This knowledge increases access to the greatest concentration of victims, exploiting the element of surprise. Perpetrators who are current students or employees at the site bypass traditional safety measures and have the opportunity to conduct detailed planning and rehearsals on a daily basis.

Law enforcement should use this information to support their local schools in developing prevention programs that seek to identify and support at-risk students while simultaneously guiding educational leaders toward effective security features. For example, there is little to no evidence that controlled entry points, metal detectors or security cameras play any significant role in preventing an attack or mitigating casualties once an attack has begun.

Assailants’ age

Facts: The age of assailants ranged from 12 to 58. Of those, 32 of the assailants (71%) were ages 12 to 18, five of the attackers (11%) were ages 19 to 21 and eight suspects (18%) were 22 years of age or older.

Implications: The majority of K-12 active shooters cannot legally purchase or possess firearms. This dramatically decreases their ability to train and become proficient in the use of firearms prior to the attack. These implications are supported by the high number of firearm stoppages observed and/or reported during attacks. Trainers should leverage this information to mentally prepare officers for the threat they will most likely encounter. The overwhelming majority of school active shooter suspects do not have the training or proficiency to stand toe to toe with officers in a gunfight.

Firearms available

Facts: During the attacks, 22 assailants (49%) only brought a handgun, four attackers (9%) only brought a rifle and six (13%) only brought a shotgun. Seven perpetrators (16%) brought a handgun and a rifle, while four assailants (9%) brought a handgun and a shotgun. One suspect (2%) brought a handgun, rifle and shotgun to the location of the attack and one (2%) brought a rifle and shotgun to the site. According to the U.S. Secret Service, nearly 80% of suspects acquired their firearm from their parents’ homes or the home of a close relative.

Implications: Handguns are the most likely weapon used in K-12 active shooter incidents. Where long guns were present with a handgun, the long gun was the preferred weapon of choice. Again, this data suggests the uselessness of overt security infrastructure, such as controlled entry points or security cameras, in detecting or preventing an attack. The majority of incidents began on campus using a concealable weapon, such as a handgun, or by concealing a long gun without being detected. Law enforcement agencies should partner with schools to explore community education campaigns that focus on the importance of securing firearms as well as the criminal and civil consequences for family members if their firearm is used during an attack.

Training should reflect the evidence with weapons used by role players or hostile targets mirroring the data. The type of firearms used should also be coupled with knowledge regarding the age and abilities of most assailants. In short, even if an officer is armed with a sidearm and facing an attacker with a rifle, empirical evidence suggests that the overwhelming majority of school active shooters lack the proficiency to gain a tactical advantage over officers.

Resolutions

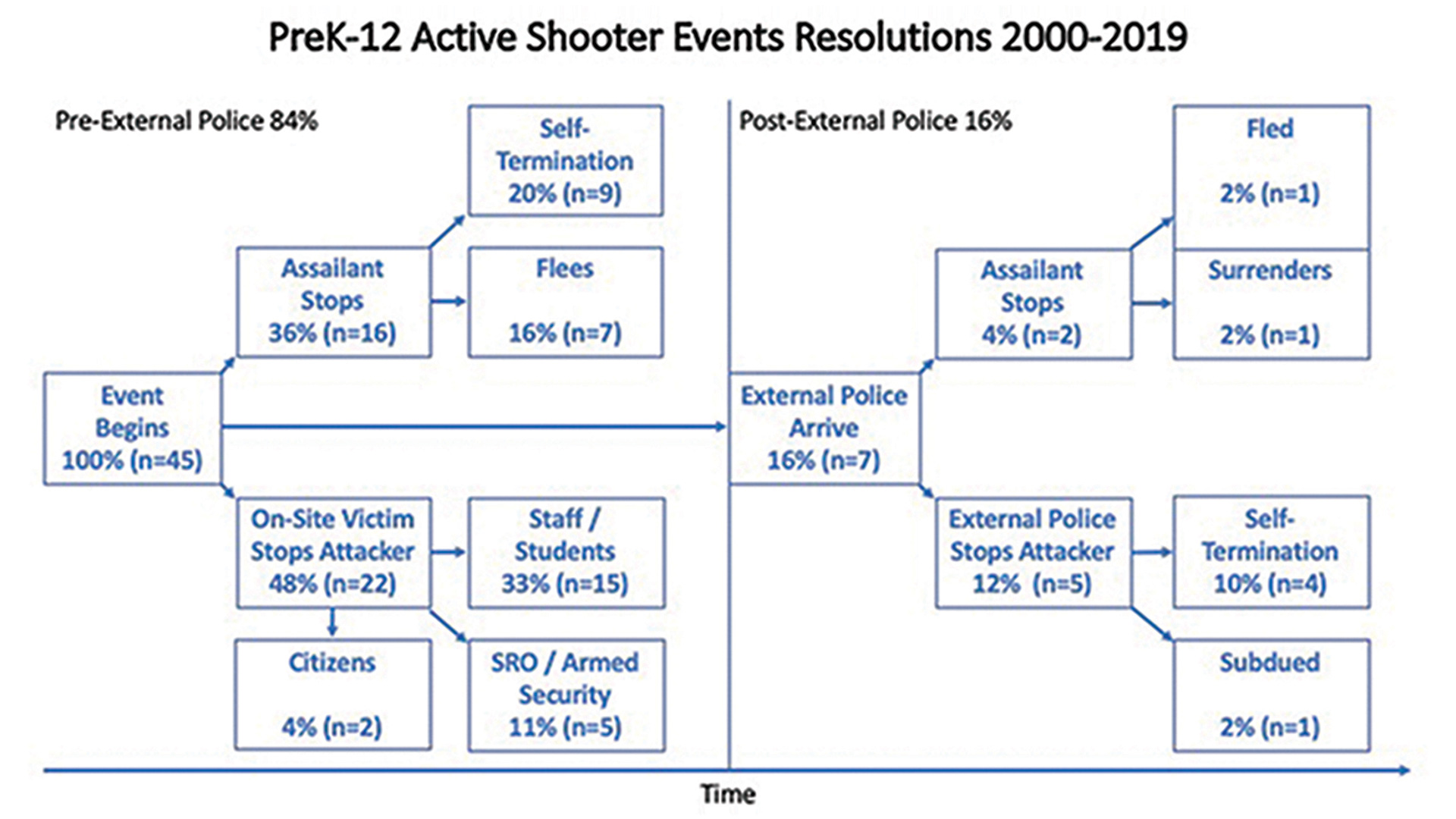

Facts: The average timeline of K-12 active shooter incidents is two to five minutes, with an average response of external law enforcement assets between six and 12 minutes. As the graphic depicts, 84% of assailants had their attacks disrupted, or had ended their attacks before external law enforcement arrived on scene. In total, 22 assailants (48%) were stopped by victims directly engaging the threat, including staff, students, on-site law enforcement or security and citizens. The majority of incidents where offenders self-terminated or fled the scene before external law enforcement arrived occurred after the attack was disrupted. External law enforcement played an active role in preventing seven attackers (16%) from continuing their assault, with four attackers self-terminating after making contact with officers.

Implications: The majority of K-12 ASIs will end before external law enforcement arrive on scene. Victim intervention was the greatest influencer in ending events. As such, officers responsible for training K-12 stakeholders in active shooter response should strongly advocate against a lockdown-only approach and encourage a multi-option response such as ALERRT’s “Avoid, Deny, Defend.” This data also supports the need to train law enforcement for a solo-officer response. Solo-officer tactics should take precedence over two-officer and team techniques. Officers should be equipped with the tools necessary to increase their confidence and safety, including patrol rifles, Level IV ballistic plates and breaching tools.

Consequences

Facts: According to the FBI, the 44 incidents resulted in a total of 241 victims. Of which, 200 victims were wounded or injured composed of 126 students and 74 staff members. A total of 41 victims lost their lives encompassing 22 students and 19 staff members. In their 2016 study exploring the wounding profile during mass public shootings, authors Smith, Shapiro and Sarani posit that the majority of victims who are killed in these attacks are shot in the head, chest and upper back. Victims with survivable wounds had an approximate 10-minute window to get to the next echelon of care.

Implications: This data also supports the need to train K-12 stakeholders in a multi-option response system. The data also reinforces the need to utilize solo-officer response tactics to mitigate the number of victims. Officers should also consider their priority of work once on scene. Although the focus should always be on stopping the threat, empirical evidence suggests most K-12 ASIs will have concluded by the time external law enforcement arrive on scene. As such, agencies should explore alternative SOPs giving officers more flexibility to begin assessing and transporting victims. The data supports a greater need for the training in and use of sucking chest wound supplies over tourniquets when treating victims at the scene of an ASI. Lastly, all agencies must critically re-examine policies that keep medical personnel in a staging area or prevent them from having the autonomy to enter an active scene during a school targeted attack.

Final remarks

School active shooter incidents are a unique phenomenon that require unique considerations in both preparation and response. Emergency studies and empirical evidence should drive our policies, procedures and tactics. Resources such as the FBI, ALERRT and U.S. Secret Service should guide us as we step outside of our emotions and challenge the status quo. This thirst for knowledge becomes even more important as schools look to law enforcement partners for guidance in this area. I hope more than anything that this data sparks difficult conversations and reflection between law enforcement leaders, trainers and frontline officers.

As seen in the October 2021 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: