Editor’s note: This article, reprinted with permission, originally appeared in two parts in the June and July 2023 issues of PORAC Law Enforcement News, the official publication of the Peace Officers Research Association of California (PORAC).

One night after responding to another death call, my wife asked me, “How was it?” My reply was almost so automatic that it startled me: “I’ve seen worse.” I wondered where that quick reply had come from.

In my service as the volunteer chaplain for the Cochise County Sheriff’s Office, I have developed relationships with the deputies during ride-alongs, meeting them at stations, being with them on training days and responding to requests for chaplain presence on a call. When I spoke with a deputy after a tough call, I would ask how they were doing. I soon learned that the typical or usual answer almost every time was, “I’ve seen worse” or “I’m OK.”

With the first answer, at times, they have undoubtedly seen worse, and in the second, they are OK, but that isn’t the whole story. I came to realize that I had begun to deal with the realities and challenges of law enforcement in the same way as the deputies. It was after my reply to my wife’s question that I began to research and think about cumulative career stress.

Cumulative career stress is a reality and a significant issue that all deputies have to deal with as part of the job.

Cumulative career stress is a reality and a significant issue that all deputies have to deal with as part of the job. This is stress that accumulates from repeated exposure to the daily demands of law enforcement. The buildup of stress can be a very subtle and slow process, but it does happen. Studies have shown that this stress is generally not recognized as an issue and that it can be easily ignored, so deputies choose to do nothing about it. In Jonathan Hickory’s book Break Every Chain, a retired police officer from the Albemarle County Police in Virginia details very candidly about the job stresses that led him to alcoholism, severe marriage and family issues, conduct issues that put his job in jeopardy and the verge of suicide. Getting to this point can be a result of not recognizing the issue of cumulative career stress and so doing nothing about it. He said: “Acknowledging the pain would only alienate me from the rest of the people in the room and crack open the door where

self-pity entered. I’d learned to keep it shut.”

I served as a U.S. Army chaplain for 26 years and started to provide volunteer chaplain coverage for the Cochise County Sheriff’s Office in 2019 as a member of the Sheriff’s Assist Team. From my Army experience, I have coined the term “the emotional rucksack” to describe the cumulative career stress that deputies experience.

For as long as soldiers have walked into battle, they have carried the needed equipment in different forms of a rucksack. Today’s U.S. Army infantry soldiers use a greatly improved rucksack that has more space but has contributed to a difficult issue. In 2017, a Government Accounting Office study determined that the rucksack weight for U.S. Army infantry soldiers was between 96 and 140 pounds and averaged 119 pounds. This carry load weight exceeds tolerable limits and has serious consequences. The study concluded that a rucksack that was too heavy resulted in significantly decreased combat mission capability and effectiveness of the soldier.

I believe the emotional rucksack presents a way to discuss how deputies carry cumulative career stress and the impacts that it has on them. Deputies see the worst of what people do to others and to themselves. The images of these calls get seared in their memories that they can’t unsee. I have heard deputies say, “I wish my mind would forget what my eyes have seen.”

As a deputy’s career continues, each call that they respond to becomes a rock that goes into their emotional rucksack. Some calls may be a small rock, and other calls may be a big rock, depending on the nature of the call. Over time as the rocks accumulate, they can be ignored as just being part of the job. While this is certainly true to a point, the emotional rucksack gets heavier with every rock. All the rocks have positive benefits and negative consequences. One benefit is that with each rock that goes into the emotional rucksack, the deputy gains important knowledge and experience that is absolutely necessary for them. Another positive benefit is that the rocks give the deputies the professional emotional distance that is required during a call. They are still human beings, but the emotional rucksack provides deputies with emotional distance from what they have seen and experienced so that they can do their job.

The challenges, issues and scenes that deputies have to witness, along with the emotions they have to control, make their emotional rucksack heavier with each shift. As the rocks increase, the negative consequences of an ever-heavier emotional rucksack can start to surface in three areas. One area it impacts is at work. A too-heavy emotional rucksack can lead to decreased job performance and effectiveness, lowered job satisfaction, indifference, lack of patience, excessive force issues and citizen complaints. Another is in physical problems. These can include anxiety, depression, sleep problems, increased alcohol use and thoughts of suicide. The last area is in problems in marriage and family relationships; deputies become more easily angered, withdrawn, have mood swings and are hypervigilant.

For major traumatic events, most law enforcement agencies have procedures, such as critical incident stress management (CISM), critical incident stress debriefings (CISD) or similar methods to address and assist those who were involved at the scene. Yet the day-to-day routine calls that aren’t considered to need this level of specific attention go unaddressed and continue to add to the deputy’s emotional rucksack.

So what can be done for this significant, easily ignored or dismissed issue? It isn’t what one deputy told me, “When your rucksack gets full, you just get a bigger one.”

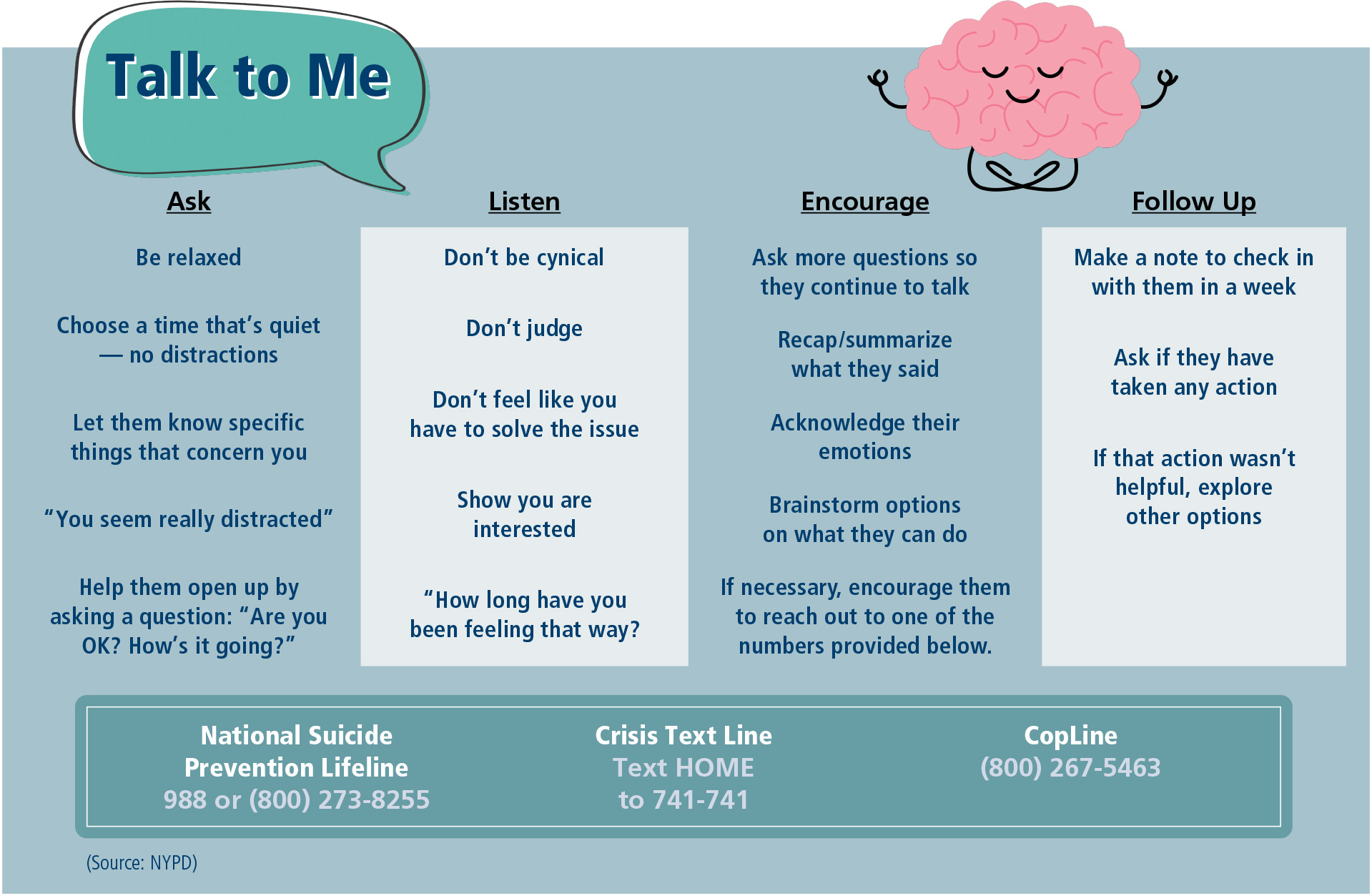

The FOP/NBC study of 8,000 active and retired sworn officers found that 73% of respondents indicated that peer support, talking to another deputy, was the most effective way to work through the stresses they face on the job. What makes this finding even more significant is that 65.4% of the officers in the study had from 16 to 25 years of on-the-job experience. While deputies have a wide variety of skills, abilities and talents, they probably don’t consider themselves to be counselors. As a result, they may be hesitant to talk to another deputy about the stress of the job. As an Army chaplain, I learned that while I could ask a soldier how they were doing, it was easy for them to hide or disguise what was happening in their lives and tell me they were fine. To other soldiers, their friends who knew them better, hiding their difficulties and thoughts was much harder. The same is true for deputies. Through spending time together during answered calls, getting coffee or a meal, they come to know each other. This puts them in a good position to know when something is just not quite right. Reaching out to another deputy can seem intimidating, risky and uncomfortable, but it can provide a way for them to talk about the challenging feelings, thoughts and emotions caused by the stressors of the job. Talking can help them put into words what is going on inside. It takes courage to reach out and talk to another deputy who may seem to be struggling, but it is important. A guide from the New York Police Department entitled “Talk to Me” provides a way for deputies to reach out to one another to help in talking about their emotional rucksack.

Deputies’ vehicles are required to have regular services and maintenance to keep them performing at their peak level capabilities and extend their longevity. It is even more important for a deputy to perform regular services and maintenance on their emotional rucksack. As they do this important maintenance, they will continue to serve at peak effectiveness and avoid the negative consequence of a too-heavy emotional rucksack.

In my 26 years as an Army chaplain, I have talked to countless soldiers, spouses and family members about the problems and issues in their lives. In these conversations, I discovered that talking does help. I don’t understand how or why, I just know that, in fact, it does.

Cumulative career stress is carried by every deputy in an emotional rucksack and is a reality of a career in law enforcement. That rucksack does provide positive benefits and negative consequences, and it reflects the rewards and challenges of caring for the people of the counties and cities they serve. Professional basketball player Kevin Love, who struggled for many years with thoughts of suicide, said, “Nothing haunts us like the things we don’t say, so me keeping it in is actually more harmful.” For deputies, not keeping it in is having the courage to talk and lighten the weight of their emotional rucksack. It can seem to be a daunting task to reach out to someone or be willing to talk, but ultimately do it for yourself, do it for your family and do it for the agency you work for.

As seen in the September 2023 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: