Since Edward Snowden rose from being an unknown NSA contractor to a household name and a polarizing archetype on privacy, there has been a paradigm shift in the way people prefer to communicate. Whether it’s in the United States or countries abroad, end-to-end encryption apps like Meta’s WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal have become some of the most utilized apps in the world on both Apple and Android platforms, often with users who prefer to communicate via the apps versus standard calling and text messaging. From a law enforcement standpoint, we see those who engage in criminal activity having a preference for using end-to-end encryption apps, believing they can circumvent lawful monitoring and intercepts. While an ill-informed perception is that end-to-end encryption apps will thwart any type of investigation, it is important for us in law enforcement to understand how end-to-end encryption apps work and, more importantly, how they can be investigated.

First and foremost, the concept of end-to-end encrypted communication is nothing new and has been around a lot longer since WhatsApp was founded in 2009! From smoke signals to couriers carrying coded letters to generals in medieval warfare, being able to privately communicate sensitive messages unbeknownst to your enemy has been a staple of combat. In fact, one of the turning points of World War II was when Alan Turing, a British mathematics genius, and other mathematicians cracked the German “Enigma” code (documented in the 2014 film The Imitation Game). Concerning the United States, the use of Navajo language as a code (highlighted in the 2002 film Windtalkers) was essentially our “end-to-end encryption” signal safeguard. Fundamentally, the basis of encryption lies in cryptography, the practice of encoding and decoding messages. If somebody were to see an encrypted text without knowing how to decrypt it, it would be unintelligible. The dawn of signals intelligence (SIGINT) wasn’t based on the interception of the signals, but the ability to decipher what was intercepted.

Misconceptions are rampant in the law enforcement community about how end-to-end encryption apps are used and how much law enforcement can really do to investigate that usage.

Spawning from Snowden’s revelations in 2012, there has been a hyperfocus on end-to-end encryption (E2E) communication in this digital age, specifically phone and emails. The widely popular encrypted email service ProtonMail went online in 2014 and has accrued over 50 million users worldwide in seven years, utilizing its wide variety of services.[1]Lomas, N. (2021, May 19). “Proton, the Privacy Startup behind E2E Encrypted ProtonMail, Confirms Passing 50M Users.” TechCrunch+. tinyurl.com/8emsz49r. By comparison, since launching in 2009 and being acquired by Meta, WhatsApp has an estimated 2 billion users worldwide,[2]WhatsApp (n.d.). “Two Billion Users — Connecting the World Privately.” tinyurl.com/yrk8u64x. followed very closely by Meta’s own Facebook Messenger with an estimated 1.3 billion users.[3]Nakutavičiūtė, J. (2022, April 11). “What is the best secure messaging app?” NordVPN. tinyurl.com/4j2vt23d. The metrics concerning other popular end-to-end encryption messaging apps like Telegram (estimated 500 million users as of 2021)[4]Schroeder, S. (2021, January 13). “Telegram hits 500 million active users amid WhatsApp backlash.” Mashable. tinyurl.com/3u6947te. and Signal (estimated 40 million users)[5]Wille, M. (2021, June 10). “Millions flocked to Telegram and Signal while Facebook was down.” Input Magazine. tinyurl.com/4bjamxmn.

reflect that communication privacy has become a paramount concern for the lay user. Rising in tandem with end-to-end encryption services, usage of virtual private networks (VPNs) as well as delineating device security (Apple iOS vs. Google Android)[6]Markuson, D. (2021, September 21). “Android vs. iOS: Security comparison 2022.” NordVPN. tinyurl.com/ck89yhf2. has also become the zeitgeist of the connected world as we know it, with Apple iMessage boasting its own standard end-to-end encryption. These statistics and trends beckon the question: What can law enforcement, often viewed as the Orwellian “Big Brother,” do to investigate end-to-end encryption services designed to thwart their efforts at every turn?

From an investigative standpoint, it is important to understand that end-to-end encryption protects the message in transport between the sender and receiver. It safeguards the data from outside monitoring and ensures security if intercepted. However, if an end user’s device becomes compromised, the messages can be read easily. For those who are mobile device examiners, popular programs like Cellebrite, Axiom, etc., parse the communications in end-to-end encryption apps linked to standard text messages and emails. While there are apps that mitigate this by requiring a password to log in, the average user does not have this enhanced security feature on the commonplace apps and rely on their device’s normal locking/unlocking for this privacy. While there are other apps boasting higher security, like Threema, or a suite of privacy oriented software, like Dust, the likelihood of a suspect using these is relatively low. While there has been widespread reporting regarding law enforcement’s ability with monitoring WhatsApp communications,[7]Kroll, A. (2021, November 29). “FBI Document Says the Feds Can Get Your WhatsApp Data — in Real Time.” Rolling Stone. tinyurl.com/mryav9zm. this seemingly has not had an effect on the volume of users.

While there is no shortage of end-to-end encryption apps available on both Google Play and the Apple App Store, more and more apps advertise that they are not based in the United States or have their servers not within reach of Five Eyes partners as a selling point. Arguably the most popular app in this category,

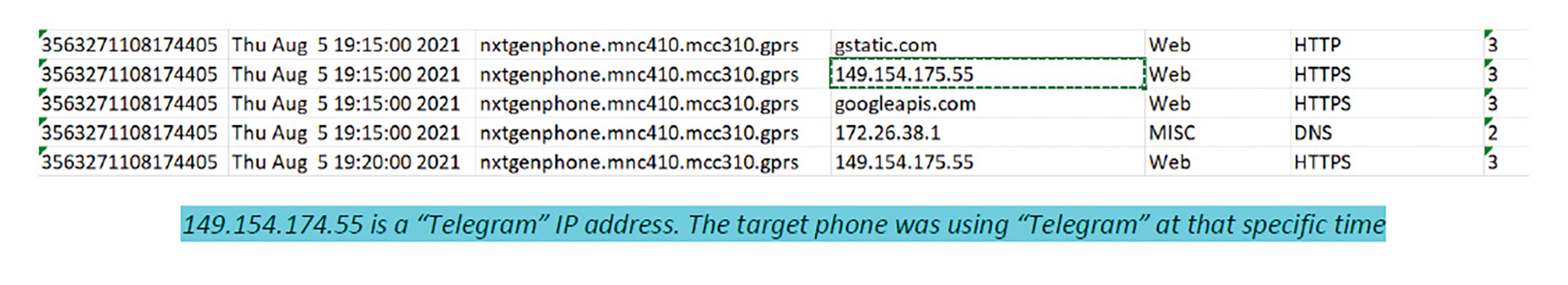

Telegram, rarely complies with legal orders unless under extreme circumstances and maintains very little information that could be helpful to law enforcement. Law enforcement often asks the question, how can usage of Telegram (or a similar app) be investigated? The answer lies in the service provider for the suspect cellphone. Mobile IP sessions and global packet radio services (GPRS) reveal when an app on a phone is using the data plan from the cellular service. While this type of data can only be compelled via a search warrant, it can be the proof that your target was using the app at a specific time in question (see Figure 1).

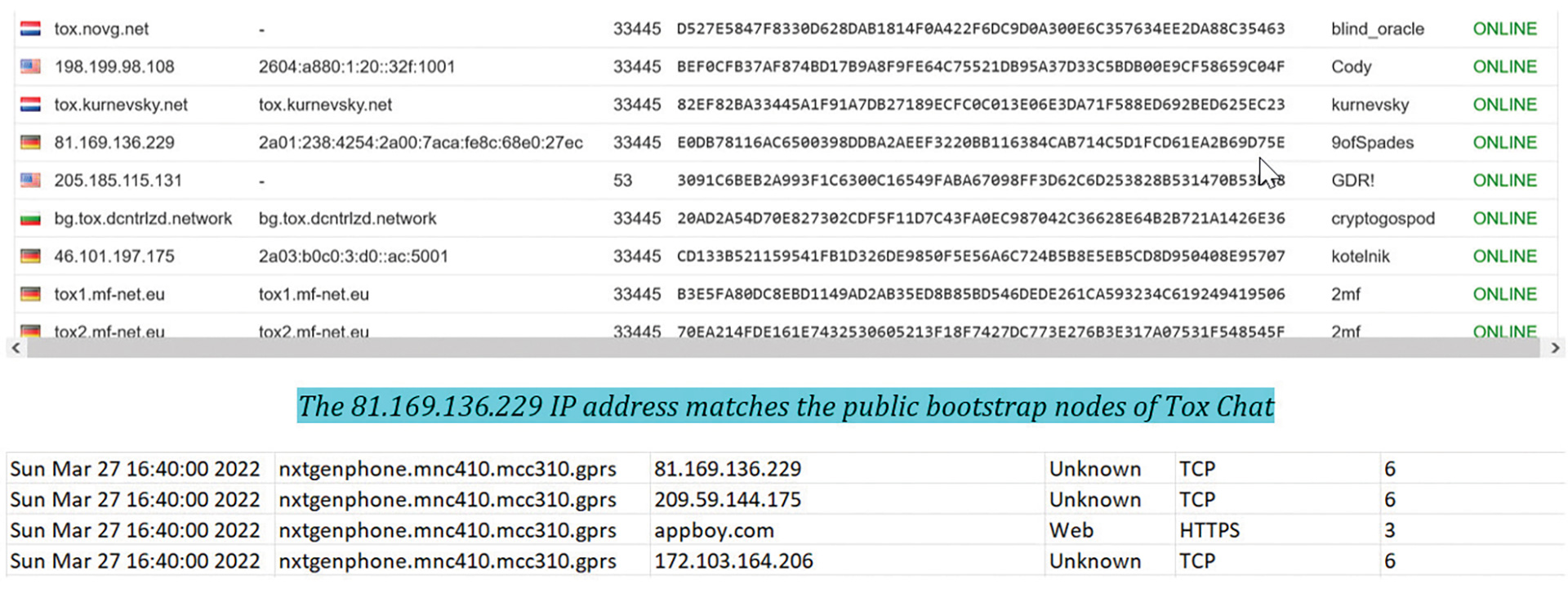

As the debate will constantly continue over which end-to-end encryption service is the “most secure,” and the best practices in general for privacy will constantly be evolving, something we in law enforcement must be cognizant of is the rise of open source and decentralized end-to-end encryption apps, like Tox Chat and Matrix. In my opinion, these pose the biggest threat, and can throw the biggest “monkey wrench” in investigations, since there is no central server but rather multiple volunteer-run support servers around the world. This is no different than the advent of the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, in that there is no centralized governance but rather miners who sustain the blockchain. From an investigative standpoint, if a suspect were using an app like Tox Chat on their phone, compelling mobile IP/GPRS sessions can prove that your target was utilizing the service at a specific date and time. Tox Chat publishes its bootstraps nodes on its website (see Figure 2).

In the constant “cat-and-mouse” game of developing technology to one-up law enforcement tradecraft, it is important for investigators to stay abreast to the current trends, especially in the way suspects may be communicating. Misconceptions are rampant in the law enforcement community about how end-to-end encryption apps are used and how much law enforcement can really do to investigate that usage. It is my hope that an article like this can help embolden law enforcement partners to pursue alternative investigatory avenues and adapt to the ever-changing landscape.

As seen in the June 2022 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below:

References

| 1 | Lomas, N. (2021, May 19). “Proton, the Privacy Startup behind E2E Encrypted ProtonMail, Confirms Passing 50M Users.” TechCrunch+. tinyurl.com/8emsz49r. |

|---|---|

| 2 | WhatsApp (n.d.). “Two Billion Users — Connecting the World Privately.” tinyurl.com/yrk8u64x. |

| 3 | Nakutavičiūtė, J. (2022, April 11). “What is the best secure messaging app?” NordVPN. tinyurl.com/4j2vt23d. |

| 4 | Schroeder, S. (2021, January 13). “Telegram hits 500 million active users amid WhatsApp backlash.” Mashable. tinyurl.com/3u6947te. |

| 5 | Wille, M. (2021, June 10). “Millions flocked to Telegram and Signal while Facebook was down.” Input Magazine. tinyurl.com/4bjamxmn. |

| 6 | Markuson, D. (2021, September 21). “Android vs. iOS: Security comparison 2022.” NordVPN. tinyurl.com/ck89yhf2. |

| 7 | Kroll, A. (2021, November 29). “FBI Document Says the Feds Can Get Your WhatsApp Data — in Real Time.” Rolling Stone. tinyurl.com/mryav9zm. |