My highway encounter and a deeper problem

I pulled off the highway into small-town Cloverdale, California, and a homeless fellow approached me.

“Do you know where there’s a grocery store?” he asked.

“How about the gospel mission and you can eat for free?” I replied.

“No, I’m not hungry. I’m new in town. I just need a new shopping cart.”

The average grocery cart costs hundreds of dollars. Yet, in communities nationwide, we’re all guilty of ignoring this constant, prosecutable crime-in-progress. We’re anesthetized to it. But just you try loading one into your pickup and see what happens.

Across major U.S. cities, patrol officers routinely handle three to four homelessness-related calls per shift, consuming an estimated two to four hours of their time — often the single largest category of service demand.[1]Based on data from San Francisco HSOC (2019), Rochester P.D. (2025) and national studies by the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty and the Central Florida Commission on Homelessness. It’s mostly unproductive, too. Nationwide, that amounts to billions of ineffectively spent taxpayer dollars. For example, in California alone, it was reported that $17.5 billion was spent on combating homelessness over four years, from 2018 to 2022.[2]Watt, N. (2023, July 11). California has spent billions to fight homelessness. The problem has gotten worse. CNN. cnn.com/2023/07/11/us/california-homeless-spending. Yet during that same period, the number of homeless individuals increased, and the state continues to add more homeless people each year than any other, with 187,000 people sleeping on the street or in shelters as of 2024.[3]Kendall, M. (2025, January 6). New homelessness data: How does California compare to the rest of the country? CalMatters. calmatters.org/housing/homelessness/2025/01/hud-pit-count-2024. But I believe that there is a novel, achievable fix for homelessness in our communities, and free carts play a central role.

Understanding the real causes of homelessness

Politicians and bureaucrats have convinced many that the cause of homelessness is a lack of housing. It’s not true. Having no home and those shopping carts are only symptoms of a deeper problem. Think about it: While it’s often reported that most undocumented immigrants live well below the poverty line, very few appear to be homeless.

The common thread with the homeless is this: their lives are untethered because they’ve lost their closest relationships with families and friends. In their steady spiral downward — drug abuse, alcoholism, relationship abuse, crime and more — there comes this flashpoint when their allies finally give up on them. The most visible result of that is homelessness. Fix these relationships and homelessness recedes.

Billions of tax dollars are spent annually, often misguidedly, on homelessness. Putting broken people in free housing may feel good, but it makes things worse. We’re doing things wrong, and because of that, we’re allowing our communities to be wrecked.

It’s an ungainly issue. But let’s simply consider cause and effect. The effect — homelessness — proceeds from the cause — broken relationships. We need a programmatic approach that heals the cause so that the effect will be healed, too.

Could our tax dollars do this? What if our civil servants, the police, social services and more could temporarily step in with the homeless where their families stepped out? Could we care for the person, have genuine interest in their well-being and recovery, and cap all this with regimented accountability? I believe that we can be a lifeline to help their essential relationships heal and their self-sufficiency be restored.

What it means to be a member of a community

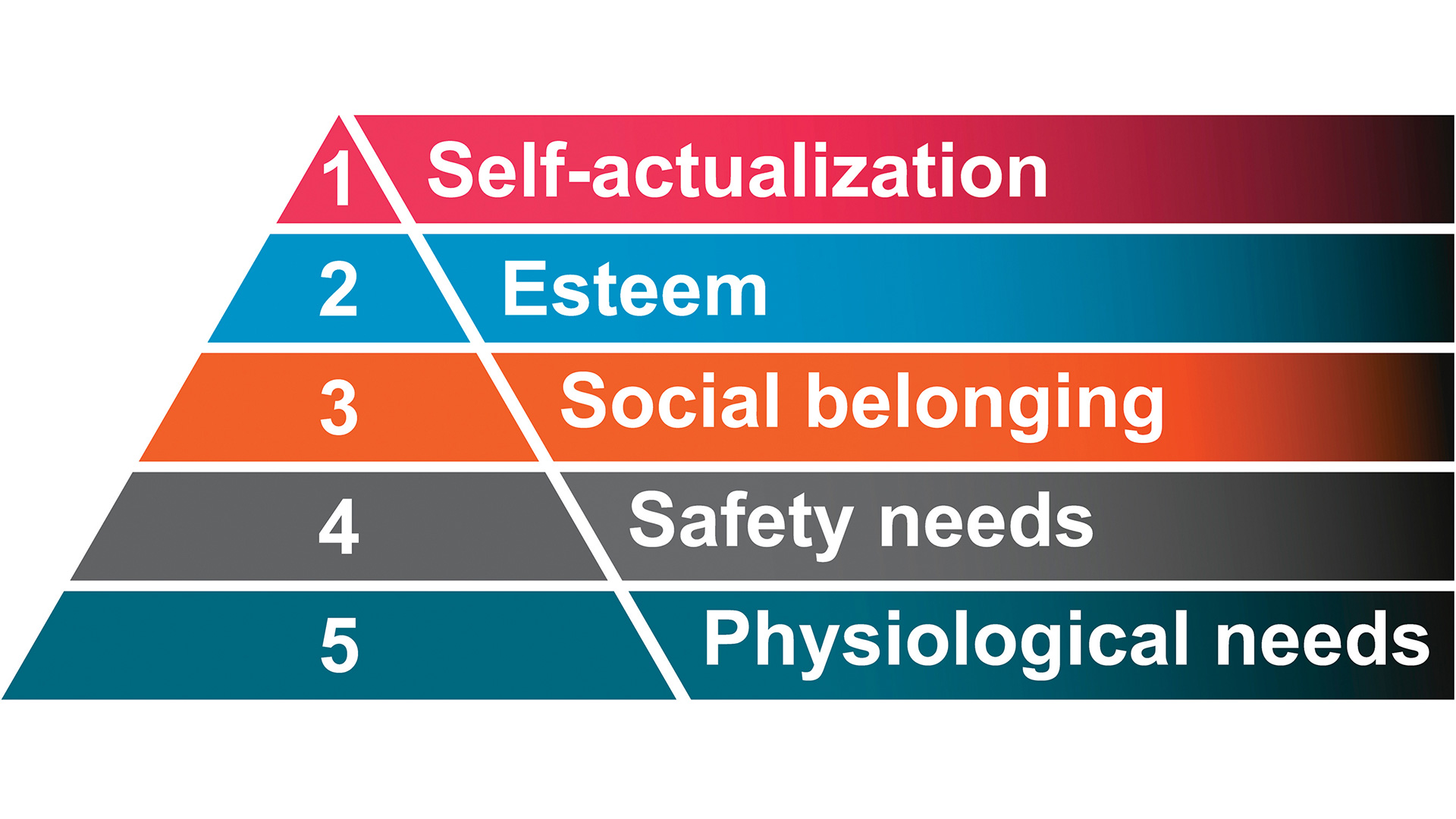

To do this, the entire community needs to buy in. Humanity coexists in communities for safety and security — the second most fundamental level of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Because of those two essential needs, as members of a community, we agree to live peaceably with one another — creating civilizations by living civilly. We constrain our primal urges and comport ourselves in such ways as to not disrupt or bother one another. As complete strangers, we are kind and considerate, and we even help one another. For the safety and security of communal living, that’s expected.

Moral guideposts for successful communities are codified into laws, regulations and policies that your high school civics teacher collectively called “the rule of law.” As fellow community members, we agree to hold each other accountable to them. For those who refuse, government in uniform (we police) mobilizes.

So why isn’t our community model working? The homeless know why: they’re really not accepted as members of our community. Stripped of Maslow’s next level, the basic human need of social belonging, they’re not held to community standards.

First from their loved ones, and then from the rest of us, the lack of accountability causes perpetual homelessness. Because relationships are voluntary (and also hard work), it’s easier for all of us to deny the unattractive homeless the privileges and expectations of community membership. Instead, we conveniently accept a lack of housing as the cause and solution to homelessness. Morally absolved, we ignore them.

A structured pathway back to community

I have an idea for a new programmatic approach. It won’t be cheap, but redistributing those incredibly expensive “housing first” earmarks will make it feel that way. Here in medium-sized Sonoma County, California, for example, in the last 10 years alone, we have spent over a half a billion dollars on homelessness. But we have little to show for it, and things just keep getting worse.

What if we could intentionally welcome the homeless back into the safety and security of community, rule of law and all? Sure, for some of them that would never work, but for many, it could.

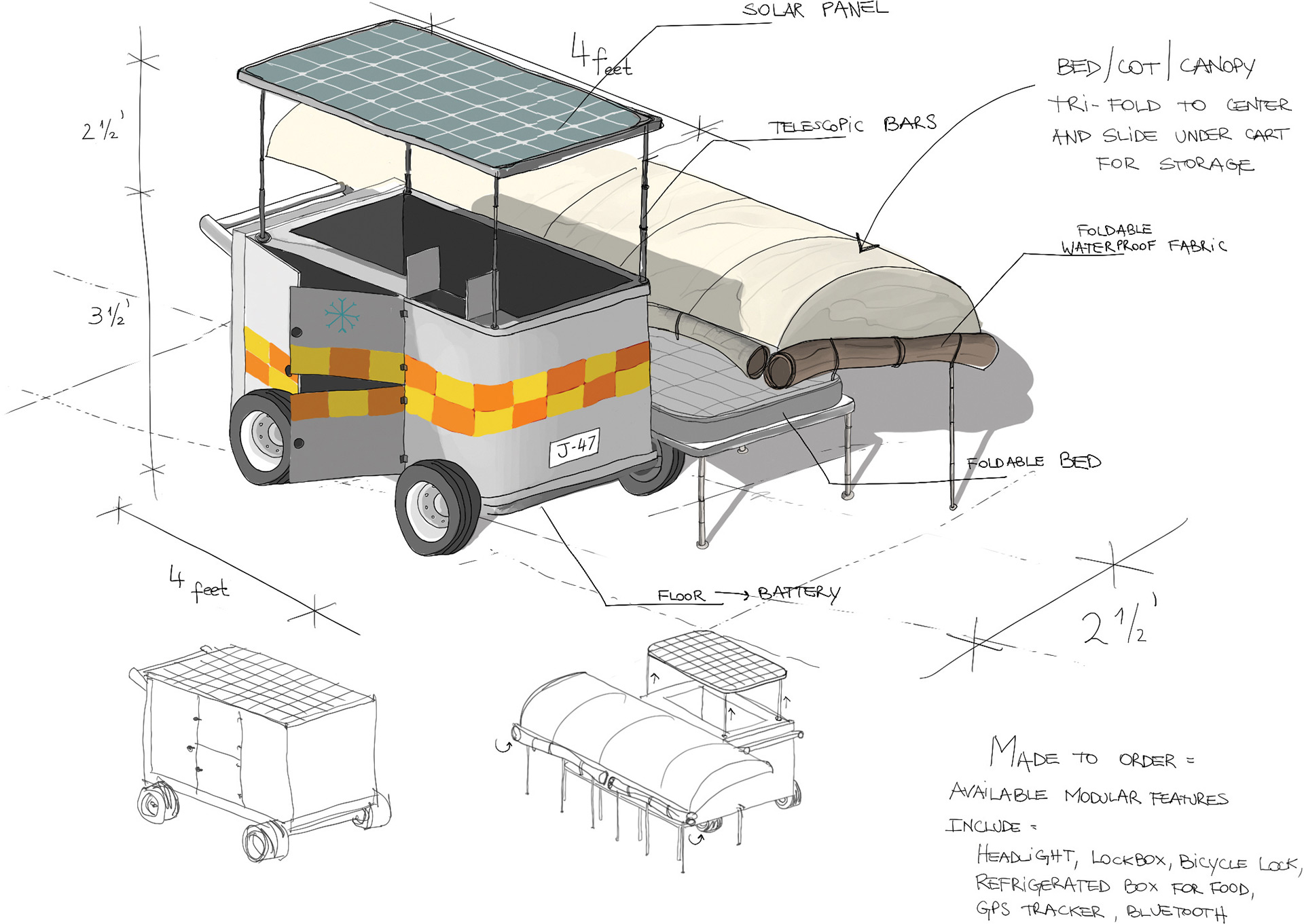

We could start with no more stolen shopping carts. They’re everywhere because they’re so necessary. How about we custom-design a more dignified and useful kind of cart that is especially made for this need, serialize them and then issue one to every homeless person who wants one? But with that acceptance, they will need to agree to some simple, reasonable terms that are designed to slowly lift them out of their terrible state — things like accepting a local government-provided sponsor (a social worker) who would become their probation officer/life coach/parental figure and set them up with mandatory job skill training, drug and alcohol detox, counseling attendance and more.

Acceptance of this GPS-trackable cart would necessitate giving up some freedoms that come with the anonymity of homelessness, but it could unlock other benefits through enrolling them in a local government-built programmatic approach to restore them to eventual self-sufficiency. It could be their gateway to government- or nonprofit-sponsored local transitional housing and more.

These carts should be readily identifiable and seen throughout the community as an honorable affirmation that their user wants back in and is willing to do the hard work to get there. Whoever accepts a cart should have to sign a pledge, one that’s hopeful and uplifting but also requires them to obey all laws, be of good conduct and cooperate with various stages of a program that leads to its eventual completion and success.

With Bluetooth signal and a mounted sign, each cart should have a short code that’s easily readable by police and social workers from a distance and allows them to quickly find the user in a database to learn personal information about them and how they’re doing in the program. Since a lot of homeless people are fearful, angry or dismissive of law enforcement, police officers especially should be encouraged to stop and check in on them in friendly ways and speak encouragements to them, too.

Here are some things our custom carts could come with:

- Lightweight but sturdy frame

- All-terrain tires

- An all-in-one foldout rainproof tent with an integrated off-ground cot, inflatable mat, sleeping bag, pillow and LED light

- Solar panel with rechargeable battery for phone and light charging

- Lockbox for valuables

- Bicycle lock

- Insulated box for food

- Flashlight that can also be mounted as headlight

- Various storage compartments

- Audible panic alarm that notifies police dispatch, plus a help flag

- 360-degree reflective siding

These modular features could be ordered and repaired or replaced individually (“a la carte”) according to local geographical needs.

Say you’re homeless and you want in the program, but don’t want a cart. We’ll assign you a backpack and bicycle with some of the cart’s features. But if we ever find you with a grocery cart, you’ll also get immediate free housing (jail).

Since the foundation to this programmatic approach is relational, churches and other local nonprofits might also be great resources in assisting this population into eventual self-sufficiency.

What about the unwilling or incapable?

Of course, there will be some homeless people who would not want a cart, nor the program that comes with it. The reasons behind such reluctance would be many. Some might be afraid, and others might be mentally or emotionally incapable. There will also be some unrepentant criminals, and then plenty who find their grocery-carting lifestyle of no job, no responsibilities, free meals, drug and alcohol abuse, and come-and-go free housing to be the good life.

This program creates new ways to effectively deal with these sorts, too. For the unwilling portion of the homeless population, by declining the conditional invitation back into civil society, they would be opting themselves into even more: daily (and nightly) attention from a fully funded problem-based policing unit. Customized to the optimal staffing necessary to aggressively address this intentionally uncooperative segment, this unit would include a 24/7 undercover unit, plus staff from the district attorney’s office who commit to file charges on every legally fileable crime — including possession of those grocery carts. As for individuals who are incapable of forming criminal intent, the criminal justice system could appropriately order them into other mandatory programs or treatments.

Do nothing, do to, do for or do with

Right now, few have any hope that this national homelessness crisis will get better. If we do nothing differently, that’s hopeless too.

Then there’s the do to approach, which presupposes that homeless people are the problem. We can punish them, marginally supply them or continue to exclude them, but then their homelessness just becomes a trap that keeps them in their cycle of despair.

Doing it for them won’t work, either. Trying to fix homelessness for them means that we believe that they are generally incapable of participating in any solutions. It’s a dehumanizing approach and one that we’re on right now. It unintentionally creates barriers to helping people overcome their homelessness.

So, we’ve tried doing nothing, doing to and doing for … all unsuccessfully. The way out of this crisis is to do with them. A “do with” approach is humanizing and empowering. So why not try this radical new way, rethinking our policies and views about the homeless — a holistic approach that invites participation from the entire community to conditionally welcome them back in?

Let me close by telling you that things in my life put me in close, regular contact with hundreds of homeless people for many years, and not just through law enforcement. A lot of them are genuinely good people who are at the end of their rope and just barely hanging on. Helping to free them feels like rescuing a hostage.

A perfect storm, but a hopeful horizon

We’ve built a system that unintentionally traps people in homelessness. Let’s build one that offers them a way out — if they’re willing to take it. As the number one community issue in countless locations, homelessness truly needs a new and novel programmatic approach. Governmental and NGO leadership certainly think so; their combined grant funding for homeless and housing assistance reportedly exceeds $40 billion annually. Especially in the current political climate, any offer from local law enforcement to help shepherd a program like this would be welcomed.

So, instead of doing nothing, let us ourselves “do with.” I’ll be happy to be the gathering point. Interested municipalities can pool their resources to author one big grant request that funds multiple simultaneous trial locations. These communities could learn from one another and help each other, too. If you think your community might be a good match, email me at dedmonds@apbweb.com and we’ll begin.

As seen in the August 2025 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below:

References

| 1 | Based on data from San Francisco HSOC (2019), Rochester P.D. (2025) and national studies by the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty and the Central Florida Commission on Homelessness. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Watt, N. (2023, July 11). California has spent billions to fight homelessness. The problem has gotten worse. CNN. cnn.com/2023/07/11/us/california-homeless-spending. |

| 3 | Kendall, M. (2025, January 6). New homelessness data: How does California compare to the rest of the country? CalMatters. calmatters.org/housing/homelessness/2025/01/hud-pit-count-2024. |