Policing the police, or creating systems for oversight and accountability within law enforcement communities, helps prevent misconduct, promotes fair and lawful treatment of the public and strengthens trust in America’s police forces large and small, among other positive outcomes.

Merrick Bobb served as the first police monitor for the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and is the founding director of the Police Assessment Resource Center (PARC), a national nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing best practices and spurring innovation in the field of police oversight. In his extensive article “Internal and External Police Oversight in the United States,” Bobb describes early police oversight as being managed by local political bosses, which often lead to corruption and ultimately to the establishment of police commissions. “The Progressive movement in the early 20th century sought to remove political influence from policing, advocating for civilian oversight by nonpartisan citizens,” Bobb states. “However, despite reforms, police commissions often lacked effectiveness due to political appointments and insufficient expertise.”

The National Criminal Justice Reference Service, established by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), was created for officers and criminal justice personnel to provide an extensive set of materials designed to enhance police professional development, management decision-making, interactions with colleagues and collaborative engagement with the citizenry meant to address job-related problems. Such issues may include preventing misconduct and abuse of power, ensuring impartial investigations, protecting civil rights, building community trust and legitimacy, improving departmental policies and procedures, providing an external venue for grievances, reducing legal liability, promoting professionalism and other related matters.

Internal affairs reports

Not all U.S. police departments have a dedicated internal affairs (IA) unit — especially smaller agencies — but most still have a process for handling misconduct. Larger departments usually maintain formal internal affairs divisions, while smaller ones rely on supervisors, the chief or outside agencies such as the state police to ensure that complaints are investigated impartially.

The U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) created a report titled “Standards and Guidelines for Internal Affairs: Recommendations From a Community of Practice.” Since 1966, the COPS Office has supported law enforcement initiatives designed to enhance community trust, and this 77-page document, produced by a project team from various police departments, focuses on internal affairs investigations “as crucial for maintaining accountability and protecting the rights of all parties involved.”

The project began in 2005 to create a platform for major city police departments to share best practices in internal affairs; however, the group discovered significant disparities in practices and definitions across various agencies, highlighting the complexity of internal affairs. The report asserted that all serious complaints must be investigated, with the scope of the investigation varying based on case complexity, and that internal affairs must ensure investigations are free from bias or conflict of interest, reporting directly to agency heads.

From the report summary: “A complete investigation gathers all relevant information necessary for a fair inquiry. Decisions not to pursue a complete investigation must be documented by Internal Affairs leadership. Serious criminal investigations should ideally be handled by a specialized Internal Affairs team to ensure objectivity. Investigators should be independent from the accused to avoid conflicts of interest. Internal Affairs should investigate serious allegations, including officer-involved shootings and constitutional violations. Complaints against command-level personnel should also be investigated by Internal Affairs, except in cases of conflict of interest.”

The report details how all interviews should be recorded and documented and that “[a]ll serious uses of force should prompt immediate investigations by Internal Affairs or specialized teams. Reviews should focus on policy implications and opportunities for improvement in training and procedures.”

Deputy Chief Beau Thurnauer of the East Hartford, Connecticut, Police Department created a similar document for the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) entitled “Internal Affairs: A Strategy for Smaller Departments.” He notes that every police department large and small will have to deal with a complaint concerning an officer’s conduct or behavior at some point. “There are those who believe that the police take advantage of and abuse their power on a routine basis. … Since law enforcement is accountable to everyone regardless of their opinion of us, we are obliged to ensure that our officers operate within the confines of the law and according to procedure. The minute we detect any violation of not only statutory rulings, but of internal policies, we must investigate the incident and bring about swift and just correction, if required.”

The nine-page guide considers administrative versus criminal complaint procedures, presenting detailed guidance for proceeding with internal affairs investigations, reliable methods of interviewing, document retention and a professional standards checklist.

Some jurisdictions empower civilians to oversee police internal affairs, such as Seattle’s Office of Professional Accountability and Los Angeles County’s Office of Independent Review, which monitor internal investigations to ensure thoroughness and fairness.

Civilian review boards

Civilian review boards (CRBs) are community panels that review complaints against police to improve transparency and accountability. Although CRBs rarely have final authority, they issue findings and recommendations to officials and the public, strengthening community involvement in policing. This approach aligns with community-oriented policing, a philosophy and strategy that focuses on building strong, collaborative relationships between police and the communities they serve. Its core idea is that public safety is most effective when officers and residents work together to identify and solve problems.

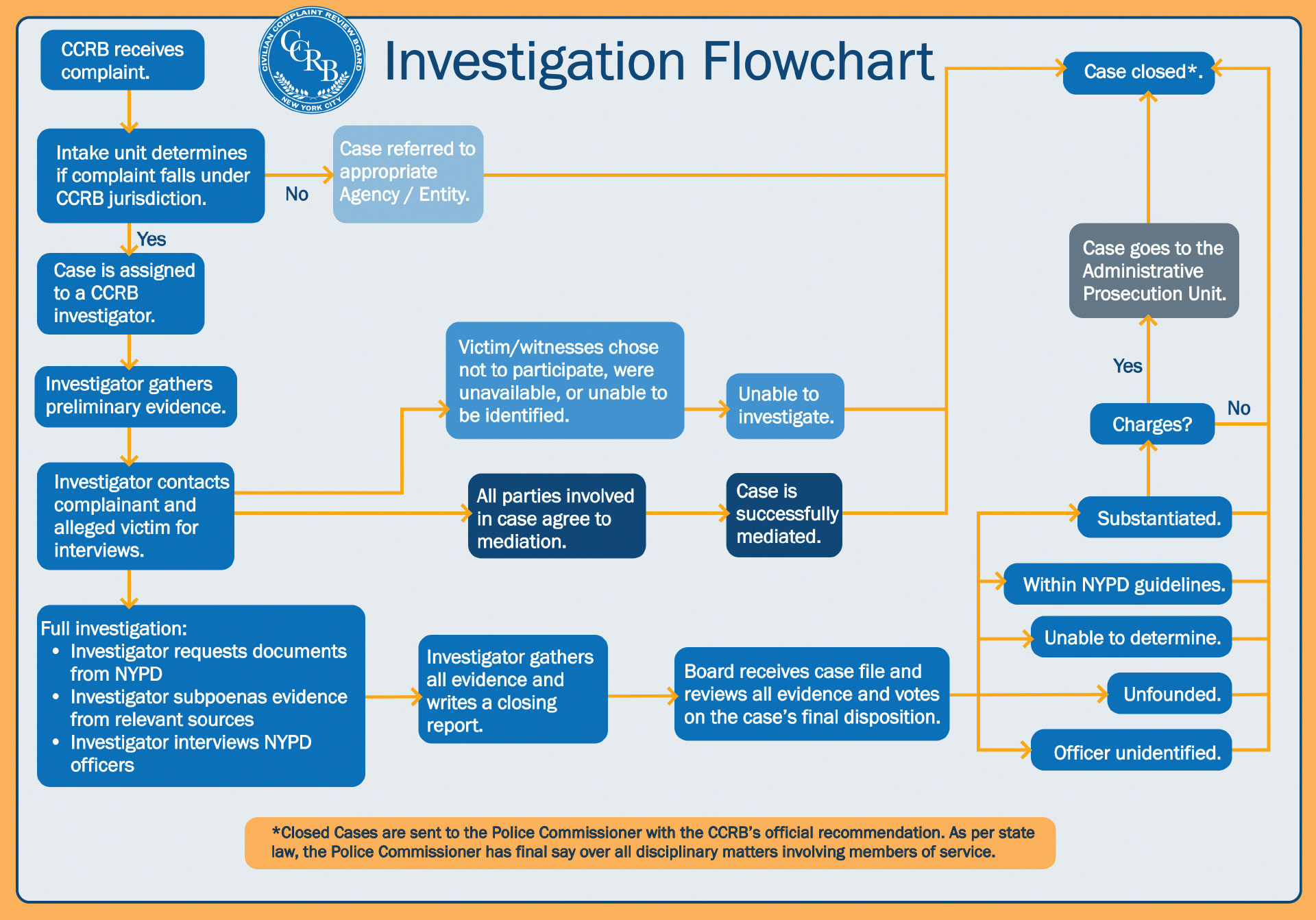

The New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) is the largest civilian oversight body for a U.S. police department, overseeing the nation’s biggest force, the NYPD, with more than 30,000 officers. It was established to investigate complaints against the police and operates with a fully civilian staff composed of 221 positions. Generally, the board handles around 5,500 complaints annually and has the authority to receive, investigate, mediate, hear and prosecute misconduct cases, recommending disciplinary actions to the police commissioner (see Figure 1).

The National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (NACOLE) identifies more than 160 U.S. jurisdictions with some type of civilian oversight body, and its data from the 2020s shows that roughly 125 U.S. cities operate a civilian review board. Research released in late 2025 reported that a little over half — about 56% — of the 200 largest U.S. cities had created some type of civilian oversight entity.

Legislative and litigative approaches

Similar to CRBs, there are a number of political organizations, generally consisting of lawyers and legislators at various levels of government, specifically focused on legal and regulatory policies designed to address and curtail police misconduct or corruption, such as the National Police Accountability Project (NPAP), a nationwide network of over 500 attorneys who have filed thousands of cases challenging police, jail and prison misconduct. In partnerships with grassroots groups, NPAP attempts to confront misconduct through litigation and legislative advocacy.

Both private citizens and government entities can initiate oversight and reform through legal action. Civil lawsuits brought by individuals can serve as a form of civilian oversight, allowing individuals to seek damages and injunctive relief. In addition, courts can mandate changes in police practices through injunctive decrees, supervised by judges.

References

Bobb, M. (n.d.). Internal and External Police Oversight in the United States. Police Assessment Resource Center. prearesourcecenter.org/sites/default/files/library/internalandexternalpoliceoversightintheunitedstates.pdf.

Civilian Review Boards. ebsco.com/research-starters/social-sciences-and-humanities/civilian-review-boards.

National Police Accountability Project. nlg-npap.org.

New York City Civilian Complaint Review Board. nyc.gov/site/ccrb/index.page.

Thurnauer, B. (n.d.). Best Practices Guide for Internal Affairs: A Strategy for Smaller Departments. International Association of Chiefs of Police. theiacp.org/sites/default/files/2018-08/BP-InternalAffairs.pdf.

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. (2009). Standards and Guidelines for Internal Affairs: Recommendations From a Community of Practice. portal.cops.usdoj.gov/resourcecenter/content.ashx/cops-p164-pub.pdf.

Winters, P.A. (Ed.). (1995). Policing the Police. Greenhaven Press. ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/policing-police-0.

As seen in the January 2026 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: