The strategy to combat drugs in the U.S. is quickly moving toward a three-fold enforcement approach that uses resources and laws to combat purveyors of narcotics. The strategy employs criminal, immigration and anti-terrorism tactics and procedures. The drug war strategy is shifting toward a comprehensive enforcement model that unites counterterrorism, immigration control and narcotics enforcement. This synergy reflects a recognition that criminal networks often operate across these domains simultaneously. State and local law enforcement departments that integrate into broader intelligence networks participate in federal-led initiatives that may require specialized training in multijurisdictional operations, combining traditional policing with national security-driven drug enforcement.

Fifty years in the making

On June 17, 1971, President Nixon gave a press conference, effectively launching America’s war on drugs in the public view. The president explained the need to target sources of drug supply worldwide while addressing drug use within the U.S.

At that time, people were using primarily marijuana, psychedelics, heroin and cocaine. Since the Nixon administration, we’ve seen nine administrations come and go with new or status-quo policies to battle and win the war. Within the U.S., the trend to fight the war emphasized a punitive program, and incarceration rates increased dramatically (tinyurl.com/4vamx6ha).

In 1982, President Reagan doubled down with his declaration on the war, which initiated rapid spending in the billions of dollars before he left office. The war on drugs led to an active U.S.–Colombia campaign to successfully dismantle Colombia’s Medellín and Cali cartels in the 1990s. The U.S. provided intelligence, training and even agents on the ground. Yet, we still see that coca production in Colombia is higher than ever before, and the U.S. remains a primary consumer (tinyurl.com/2nua7334).

A big boost to what is the second tier of the three-fold enforcement strategy came during President Clinton’s administration. In 1996, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) blended immigration and criminal enforcement by broadening felonies to be included in deportable offenses. Following the terrorist attacks on 9/11, the Patriot Act expanded law enforcement powers to investigate terrorist activities and allowed for drug investigations. This smoothed the way for the strategy we see taking shape now at the intersection of the three-fold enforcement approach. Earlier this year, the Department of State designated six Mexican cartels (tinyurl.com/39kk57jm), one Colombian, two Venezuelan criminal organizations and several other Central American gangs as foreign terrorist organizations (FTO).

New strategy

Over 50 years after Nixon’s announcement, the U.S. has spent over $1 trillion on the war on drugs, and that number keeps growing. Today, we still see the same drugs that concerned the Nixon administration being used and abused, but now it is even worse. Consider that American law enforcement must deal with the addiction, trafficking, dealing and adverse health effects of additional drugs like methamphetamine, fentanyl, psychoactive drugs, synthetic cannabinoids and the illegal use of numerous prescription medicines on the streets. Plus, the price for illicit drugs continues on a downward trend, while potency is up (tinyurl.com/5ctsxxn8).

To change the war on drugs policy, the current administration took unprecedented steps earlier this year, mainly focusing much of the attention on Mexico’s historically problematic criminal organizations. First, the administration set in motion the “total elimination of cartels” strategy. First, the administration set in motion the “total elimination of cartels” strategy. Second, the administration designated six Mexican cartels (tinyurl.com/3p35tfpr), and four Central American (tinyurl.com/2warrzp7) criminal organizations as FTOs, which enhances law enforcement and prosecutorial authorities against anyone assisting in cartel crimes.

It didn’t take long for terrorism charges to be levied against cartel members. This past September, a grand jury indicted Oscar Manuel Gastelum Iribe on terrorism charges for his drug distribution in the Chicago area (tinyurl.com/fpcstnt3).

Mexican cartels diversified their revenue streams long ago, making these organizations complex and flexible, and their illicit activities go beyond drug smuggling and trafficking in the U.S. An FTO designation opens options to take action against these new revenue streams. Third, working with Congress, the president signed into law H.R. 1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (tinyurl.com/tw78v2ex). H.R. 1 appropriates billions of dollars toward assisting state and local law enforcement efforts in the war on drugs and marries support for immigration enforcement.

The war on drugs has essentially been a 50-year intractable conflict rooted in supply and demand economics. The new strategy concentrates on eliminating cartels from the landscape of illegal drug smuggling and trafficking, thus cutting off supply to the U.S. Although we see new criminal organizations targeted in the war, like Venezuela’s Cartel of the Suns and Tren de Aragua, U.S. law enforcement is most familiar with the multiple criminal organizations that are embedded in the social fabric of Mexico, while having their agents working in cities across the country (tinyurl.com/bdzdu95d).

Criminal organizations such as (but not limited to) the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Sinaloa Cartel and Gulf Cartel dominate the manufacture and distribution of many drugs to the country. They also entrenched themselves as quasi-governments within Mexico. Their ability to exert territorial control, impose laws and rival state authority raises the question of whether a narco-state is emerging. The designation of six major Mexican cartels as foreign terrorist organizations underscores a grim reality: whether the Mexican government, especially at the state and local levels, has the capacity to function as a sovereign authority.

Over 50 years after Nixon’s announcement, the U.S. has spent over $1 trillion on the war on drugs, and that number keeps growing.

Outlook

The three-fold approach leverages multiple efforts, utilizes administrative law enforcement to support criminal enforcement, and targets cartel members for terrorism charges. Targeting specific cartels benefits American law enforcement agencies with federal dollars used for programs like Stonegarden, Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS), the Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant (JAG) and training opportunities through the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC). It is important to note that just because you target a specific cartel, remove leadership and ultimately dismantle that criminal organization, the criminal activity does not cease.

However, there are some challenges for state and local agencies in participating in the new strategy. The primary challenge is the political landscape that may determine to what extent federal, state and local agencies can work together. A former Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) official indicated that some states limit federal and local agencies from working together. Connecticut’s 2013 Trust Act restricts local law enforcement from detaining arrested individuals for federal officials unless convicted of certain felonies (tinyurl.com/5atn7kt2). According to the official, “In 2019, state legislators felt that ICE was still able to locate and arrest foreign nationals through communication with municipal and state law enforcement agencies, so additional language was added to the Trust Act with the intention of further restricting communication and cooperation between the parties.”

Lessons learned

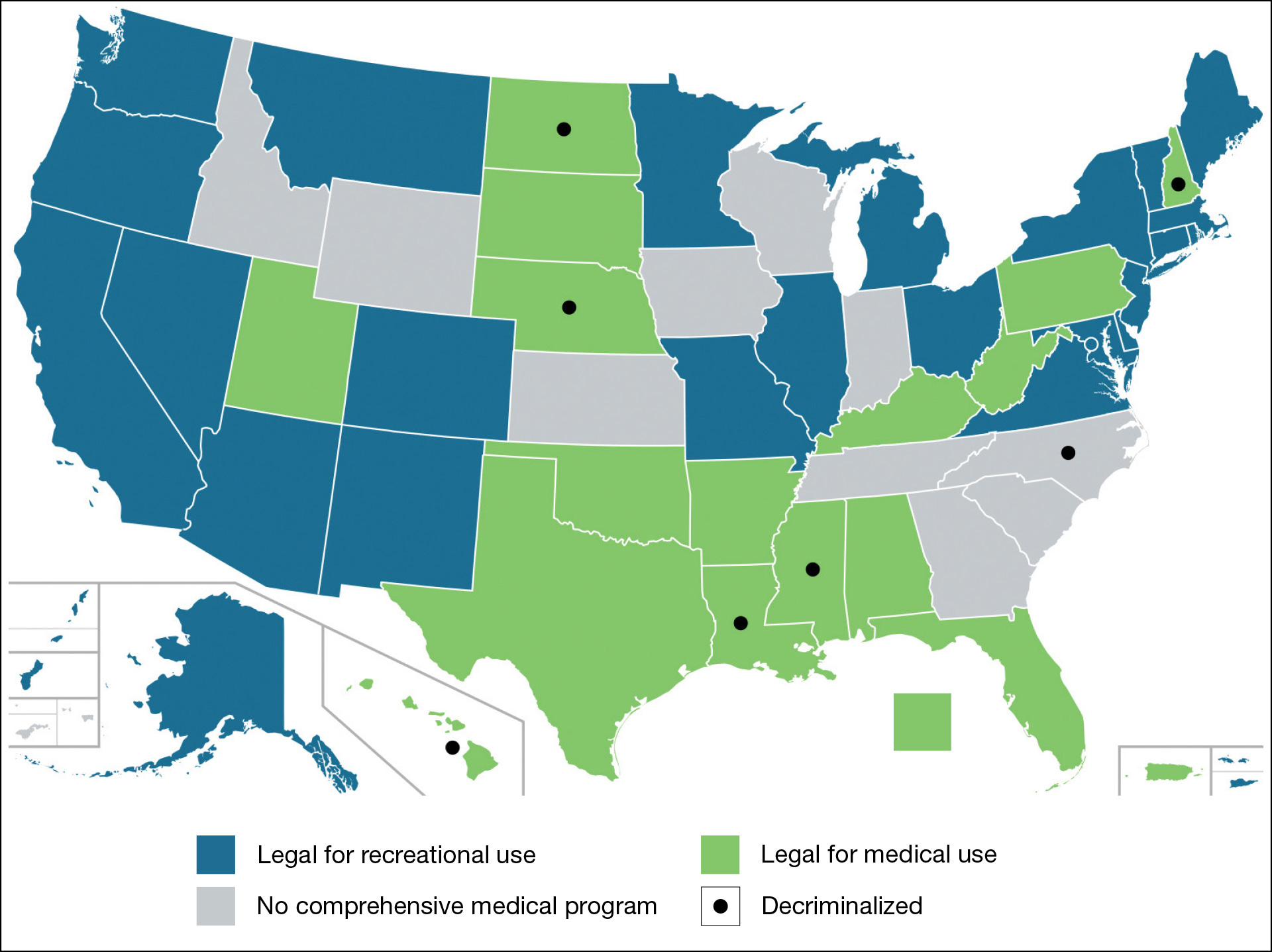

Utilizing the strategy to take down Colombia’s Cali and Medellín cartels did not solve the drug problem nor reduce the availability of cocaine for any extended period. The kingpin strategy in Mexico only created more violence, more crime, more money for criminal organizations and more fragmentation. Removing an organizational name does not stop drug production, smuggling, trafficking or use. In fact, drugs are widely available and in more varieties. Consider that marijuana, for decades, was known as the “gateway” drug. Marijuana is legalized in many states and the recent fast-tracking of a reclassification of marijuana from a Schedule I drug to a Schedule III drug should raise questions for law enforcement leaders regarding resource allocation to other anti-narcotics efforts (tinyurl.com/ye9njrj7). Law enforcement leaders may want to take a closer look at states where legalization has taken place and see how to weigh in as the war on drugs strategy changes.

Similarly, Mexico’s 2006 war against organized crime, with U.S. assistance, unleashed an unprecedented wave of violence, fragmentation and cartel proliferation; an escalation that few could have foreseen and one of the reasons why this new U.S. strategy is so important. As law enforcement leaders contemplate this strategy, along with federal enforcement efforts operating throughout the country at new levels, engagement with partners becomes even more important.

Conclusion

Rather than treating terrorism, narcotics and immigration violations as separate domains, U.S. policymakers and law enforcement agencies eliminated siloing and instead merged past frameworks into a unified enforcement model. This integrated approach leverages anti-terrorism, criminal and immigration law to fight the war on drugs. But it is still in progress, and there must be a multifaceted enforcement partnership that includes U.S. state, local and trusted international collaborators.