Editor’s note: This is part 2 of a nine-part series reflecting on the September 11, 2001, terror attacks ahead of their 25th remembrance this year. Retired Port Authority Police Officer Bobby Egbert, a 9/11 first responder veteran, examines the lasting impact the attacks had on the law enforcement profession and the ways our country and world were changed forever.

Ground was broken in Arlington County, Virginia, for the construction of the Pentagon on September 11, 1941. For 60 years, the headquarters of the U.S. military stood, not only as a testament to the might of the greatest military in world history, but as a symbol of the impenetrability of our nation.

On September 11, 2001, that reassuring confidence was shattered when enemies of America attacked the Pentagon by crashing a hijacked American Airlines Boeing 757 into the south side of the building.

The attack was not the work of a military power but of 19 men with a twisted ideology and a hatred for America who were followers of a man who lived in a cave in the mountains of Afghanistan. The statement made with that attack resonated through all peace-loving countries.

Pentagon Police Officer Linwood Barrett was on the job for 10 years after more than 22 years in the Army. He recalled being in his chief’s office when they learned of a plane flying into the World Trade Center. Like everyone, they were thinking it was an accident. When reports of the second plane developed, the chief said, “This is no accident!” and immediately responded to the Secretary of Defense’s office to secure his safety.

Barrett, who was a member of the Pentagon Police Department’s Anti-Terrorism Force, quickly went to his office in Federal Building No. 2, known as the Navy Annex, to stand up the department’s emergency operation plans. It was soon after that he heard another officer who saw American Airlines Flight 77 heading directly toward the Pentagon yell, “Incoming!, incoming!” Barrett turned, saw the aircraft hit a telephone pole and crash into the south side of the Pentagon.

Barrett and his team hurried to the site, entered the building and began rescuing the trapped and injured, many whom were suffering critical burn injuries.

After more than 22 years as a soldier and 10 years as a cop, he was faced with what he described as “nothing I ever experienced in my entire life.”

As first responders from Virginia, Washington, D.C. and Maryland swarmed the site, Barrett coordinated a perimeter around the Pentagon. In the frenetic, confusing environment, a distraught young man ran toward the perimeter yelling, “My sister, my sister is in there!” and tried to break through the perimeter numerous times. Each time, he was thwarted by the officers blocking his way. On his final attempt, he broke through the bulwark of cops. Barrett ran, tackled the young man and tried to calm him. He asked for his sister’s name.

Barrett knows he did what he had to do, but said, “to this day, it haunts me.” The sister’s name was on the list of the dead.

Arlington County Fire Department Captain Fred Kawatsky was a 22-year-old probationary firefighter, only months out of the Arlington County Fire Academy, the morning of September 11, 2001. He was the new guy on his crew in Station 4 and was listening to senior firefighters watching the events unfolding in New York City, discussing the struggles New York City firefighters were facing. They were soon dispatched to a structure fire from which they were diverted to the Pentagon on a report of a plane crash.

His unit was one of the first fire apparatus on the scene. The crew began going through the rubble, looking for survivors. Kawatsky recalled that as they made entry and began removing debris, searching for signs of life, he uncovered a portion of a body, “from the belly button to the knees, dressed in black Joe Boxer shorts.” He also entered a destroyed office where he was confronted by two males and a female sitting at a table, clothed in civilian attire, dead. He said, “They were frozen in time, and I still vividly see it. It is there forever, pure sadness.”

The Arlington County Fire Department was on scene for two weeks doing recovery work in what was a collapse zone. The recovery operation required shoring up the floors above the crash site. FEMA assigned engineers to assist the firefighters in the shoring operation.

As the site was declared secure, firefighters began recovering more bodies and body parts. When found, FBI agents photographed and documented the recovery. After the agents completed their task, the U.S. Army Old Guard (3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment) would perform a dignified transfer to the morgue facility.

“A baptism by fire” is how Kawatsky views his time at the Pentagon as a young, unseasoned firefighter. And, as “the kid” on a crew of much older and experienced firefighters, he quickly learned that the mentality he needed was to take the things he saw and did and “shove it down deep, lock it up and hope it stays locked up.” He did, though, say he doesn’t see the Pentagon today as it appears, but still through the eyes of that 22-year-old firefighter.

Pentagon Police Officer Donald Behe, a retired Marine Corps lieutenant colonel, was a young man during the 1977 Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Flood, which killed 76 people and injured more than 2,700. Johnstown is also Behe’s hometown. He also survived war deployments in Grenada and Desert Storm. His experiences in a natural disaster and wars did not prepare him for the attack on the Pentagon.

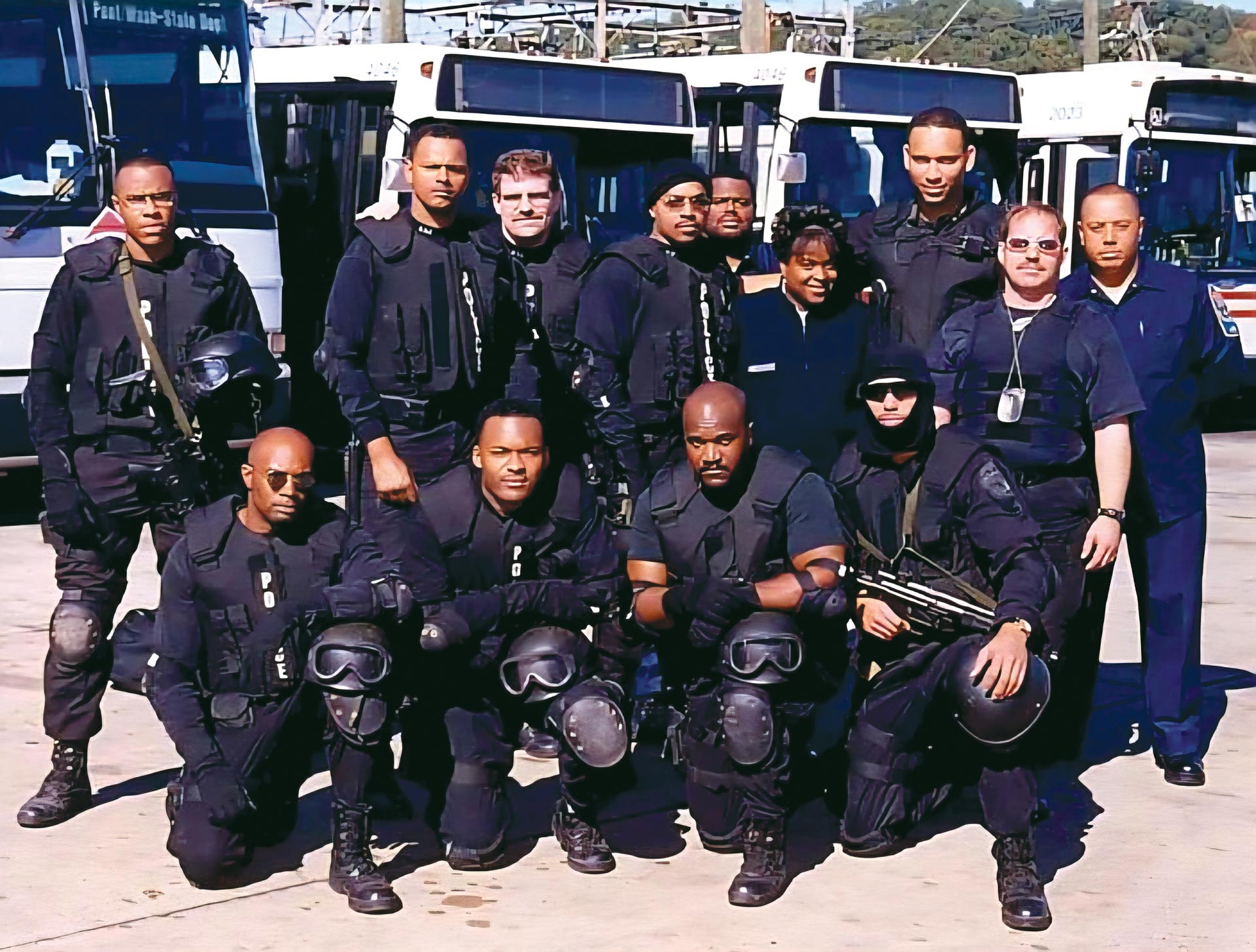

Behe, a member of the Pentagon Police Emergency Response Team (ERT), a tactical and special weapons unit, started his day on September 11, 2001, at the DeLorenzo Pentagon Health Clinic on the banks of the Potomac River, arranging for an EMS unit for President George W. Bush’s arrival on the Pentagon helicopter pad. The president was due to land on Air Force One later that day at Andrews Air Force Base, where he would board Marine One to travel to the White House. That plan was amended because of an unrelated White House ceremony diverting Marine One to deliver the president to the Pentagon.

Behe was occupied with the details of the POTUS movement when he became aware of the first attack on the World Trade Center. Watching the second attack unfold on television, he declared, “We are at war!” and responded to the building the ERT worked out of. Suddenly, the police radio was blasting, “Plane hit the building, Plane hit the building!”

Once on scene, Behe and his team were faced with a conflagration and destruction of a section of the Pentagon. He said they saw the aircraft’s fuselage that penetrated the first three rings of the five rings of the Pentagon. Though they couldn’t enter the 757, they knew all aboard were dead.

The team rescued wounded people in the ruins and noxious environment. Eventually, they climbed the stairs to the fifth floor, where they joined Arlington County firefighters and Virginia State Troopers desperately trying to rescue those trapped in the destruction. The air was acrid and made breathing difficult. A Virginia State trooper fell unconscious, overcome by aviation fuel fumes, toxic smoke and airborne particles of building materials, asbestos and human remains. Behe rescued the trooper by carrying him in a fireman’s carry down five flights of stairs. The trooper recovered after four days in a coma.

Behe, who was a Force Recon Marine, used his more than 30 years of military and police training to rescue an individual who was placed in an extraordinary incident. His actions were rewarded with a Secretary of Defense Medal for Valor.

Behe said his experiences have taught him, “If someone wants to kill someone, there isn’t a damn thing to do to stop someone who is willing to die for their cause.” What perplexes him, though, is the reported lack of intelligence sharing. During his career, he spent time working in the Defense Intelligence Agency, an experience that led him to say, “I couldn’t tell you what the rationale for not sharing was.” A thought that has occupied the minds of many.

Linwood Barrett, Fred Kawatsky and Don Behe are among those who fought the first battles of the Global War on Terror, with selfless courage and dedication to upholding the sacred oaths they swore. They took their heroic stand at our nation’s military headquarters in determined actions to never, ever surrender. They are true American heroes.

As seen in the February 2026 issue of American Police Beat magazine.

Don’t miss out on another issue today! Click below: